Dembski’s Theodicy in Dialogue with Domning and Hellwig’s Original Selfishness: A Potentially Fruitful Approach to Understanding the Intersection of Evolution, Sin, Evil, and the Fall

Abstract: In this article, I bring into dialogue two recent positions that take the problem of evolution, sin, evil, and the Fall seriously. The first William A. Dembski’s theodicy as defended in The End of Christianity: Finding a Good God in an Evil World and the second Daryl P. Domning and Monika Hellwig’s “Original Selfishness” as argued in their work, Original Selfishness: Original Sin and Evil in the Light of Evolution. In each respective account, the authors explain how sin, evil, and the Fall correspond together with respect to a scientific understanding of evolution. First, I will provide a synopsis of each position. Second, I will bring them into dialogue on the following fundamental points: creation and evolution, creation exnihilo, biological evolution, monogenism versus polygenism, the problem of evil and original sin, moral evil and original sin, natural evil, interpreting Genesis 1-3 and related themes, beyond biblical literalism, a common desire for affirming a concrete historical past, the purpose of the doctrine of original sin, the retroactive effects of the Fall, and a Kairological reading of Genesis 1-3.

Keywords: creationism; Daryl Domning; evil; evolution; the Fall; Genesis; Monika Hellwig; monogenism; original selfishness; original sin; polygenism; science-theology interaction; sin; theistic evolution; theodicy; William Dembski

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges currently facing the Church is how to understand the entry of sin into a world that was originally created good, particularly in light of biological evolution and its relation to morality and free will. A satisfactory response to this challenge has not been forthcoming, despite the great efforts made over several decades to understand such a perplexing theological impasse. However, there have been two significant contributions in recent years that have undergone this seemingly recalcitrant challenge.

The purpose of this article is to bring into dialogue these two recent positions, which take the problem of evolution, sin, evil, and the Fall seriously. The first, William A. Dembski’s[i] theodicy as defended in The End of Christianity: Finding a Good God in an Evil World, and the second, Daryl P. Domning[ii] and Monika Hellwig’s[iii] “Original Selfishness” as argued in their work, Original Selfishness: Original Sin and Evil in the Light of Evolution. Domning and Hellwig, advocate that evolution gives rise to selfish behaviours, in all organisms, including humans. They further argue that such an account is more compatible with “traditional” Christian theology than those recently offered by “evolutionary” theologians.

It is worth noting that Genesis 1:1–2:3 and Genesis 2:4–25 allow for a number of differing interpretations with respect to understanding human origins. Some of these interpretations include the following perspectives: young earth creationism, old earth creationism, naturalistic evolution, and theistic evolution (encompassing non-teleological evolution, planned evolution, and directed evolution). It is important to note that each of these positions possesses its own set of challenges, whether scientific, philosophical, or theological. Discussions revolving around the mechanisms (natural selection, random mutation, self-organization, symbiosis, hybridization, horizontal gene transfer, etc.) of evolution (i.e., how it happened) will be left aside for the most part, unless appropriate. While keeping these distinctions in mind, how does one now make sense of original sin and the fall in light of evolution? Regardless of the approach one chooses to adopt, these concepts, when drawn together, inevitably give rise to the problem of evil (both natural and moral). It is indeed a problem for Christian theology, one that cannot be simply swept under the rug. Regardless of the approach one chooses to adopt, these concepts, when drawn together, inevitably give rise to the problem of evil (both natural and moral).

A fundamental point of agreement between these two outlooks is that humans that originally bore the full image and likeness of God, in order to have the ability to sin, would be morally self-reflective agents. There is nothing in evolutionary thought, whether through the modern or extended synthesis, that precludes this. Although Darwin himself and subsequent evolutionists have held that the difference between humanity and animals was in degree, not kind, such debates regarding continuity versus discontinuity between humans and their precursors seem inconclusive at the present moment. It could be that either consciousness itself is an emergent property of the brain or that God intervened at a certain moment to create this immaterial aspect of humanity. Both of these options, the former being monistic, which includes Christian adherents such as the philosopher Peter van Inwagen, and the latter, dualistic, with supporters such as medical doctor, bio-physicist, and geneticist Francis Collins, are viable options for the Christian believer. Despite the anatomical continuity between humans and their precursors, there is a fundamental disjunction in terms of the degree to which consciousness is possessed.

Both of the relevant outlooks assume Darwinian mechanisms in order to materially explain how evolution took place. Domning and Hellwig’s perspective invokes strictly Darwinian mechanisms, whereas Dembski’s is malleable enough to encompass other potential explanations.[iv]

Synopsis of Dembski’s Theodicy

Dembski’s theodicy takes a traditional approach to explaining original sin, evil, and the Fall. Dembski’s goal[v] of building a coherent theodicy is to argue that the following three claims are true:

- God by wisdom created the world out of nothing.

- God exercises particular providence in the world.

- All evil in the world ultimately traces back to human sin.[vi]

Dembski sees the first claim as having fallen into disrepute among some contemporary theologians, namely that God created the world ex nihilo and possesses the traditional attributes. For instance, God’s attributes as developed in process theologies may preserve His omnibenevolence but compromise His omniscience and omnipotence. So, essentially, we are left with a God who is good but is incapable of overcoming evil in the world.[vii] With respect to the second, Dembski distinguishes general providence from particular providence. A god of general providence may create and calibrate the laws of physics, but beyond that, he does not intermingle in the affairs of the universe, such as the prayers of conscious beings that were the eventual unintended results of natural evolutionary processes. Claim 3 is the most difficult to demonstrate since mainline contemporary intellectual thought precludes the tenability of such a proposition by favouring an autonomous world. Although claims 1 and 2 are resisted in order to preserve God’s goodness, Dembski argues that if it can be demonstrated that evil does not result from the world’s autonomy, then there’s no reason to contract God’s power. From there, he then reasons that the plausibility of claim 3 allows for the viability of 1 and 2.[viii]

Dembski’s concern is not necessarily with the ultimate origin of evil but with providing a plausible explanation for its traceability to human sin. He sees humanity acting as gatekeepers through which evil passes into the world.[ix] In such a view, the Fall is a failure of the gatekeepers, as he states: “This metaphor [of gatekeeper] works regardless of the ultimate source of evil that lies outside the gate (be it something that crashes the gate or suborns the gatekeeper or both).”[x]

The key component of his theodicy is that “the effects of the Fall can be retroactive as well as proactive (much as the saving effects of the Cross stretch not only forward in time but also backward, saving, for instance, the Old Testament saints).”[xi] He refers to this as a doctrine of divine anticipation. Dembski argues for its coherence with both the age of the universe and evolutionary theory. As we will see, this is one of the major points of discord with Domning and Hellwig’s position. So, how does Dembski develop these remarkable claims? Before we proceed, it is important to realize that although Dembski utilizes the findings of science, he makes explicitly clear that his theodicy looks towards the “metaphysics of divine action and purpose” rather than science.[xii] To be clear, he is not bucking up against modern scientific findings but rightly pointing out that his claims, once properly understood, are metaphysical.

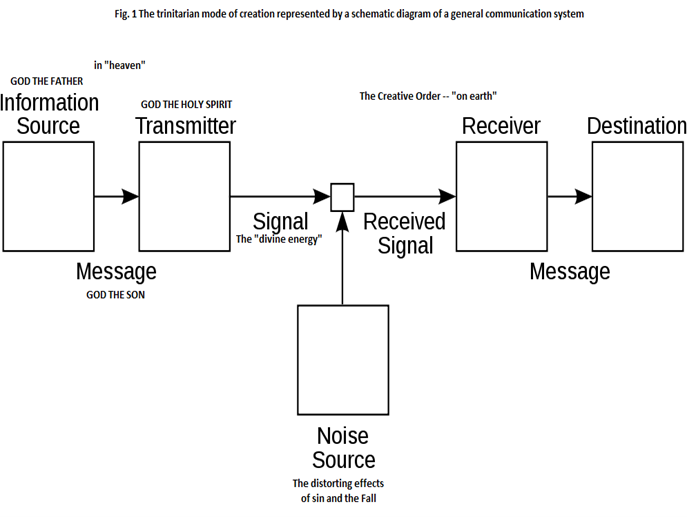

One of the innovative components of Dembski’s theodicy is the utilization of what he calls the Trinitarian Mode of Creation (please see figure 1 below). Dembski demonstrates a deep correlation between this mode of creation and “the mathematical theory of information”[xiii] as developed by Claude Shannon in his 1949 book, The Mathematical Theory of Communication. In a nutshell, Dembski associates God the Father as the information source; God the Son represents the message through Jesus, who is the incarnation of the divine Logos; and the “transmitter” represents God the Holy Spirit, taking the message and empowering it.[xiv] From there, the message is to be transmitted to its receiver and destination via a component known as the “signal,” which entails the “divine energy,” which represents God’s activity in creation.[xv] A theologically significant aspect of this communication system is the component known as the “noise source,” which Dembski explains as “the distorting effects of sin and the Fall, which attempt to frustrate the divine energy. Hence, in the Lord’s Prayer, ‘thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven’.”[xvi]

Directly related to this transmission of information from the Holy Trinity to creation is the nature of information. Dembski makes the point that the material medium where information can be located can always be destroyed, but the information itself is indestructible. He argues that the information by which God created us is indestructible despite the effects of sin that distort such information. The ultimate source of information is the divine Logos, which provides a reliable source for the intelligibility of the world. Despite this intelligibility, much of our knowledge seems distorted, which Dembski attributes to the effects of the Fall, as he states:

At the heart of the Fall is alienation. Beings are no longer properly in communion with other beings. We lie to ourselves. We lie to others. And others lie to us. Appearance and reality, though not divorced, are out of sync. The problem of epistemology within the Judeo-Christian tradition isn’t to establish that we have knowledge but instead to root out the distortions that try to overthrow our knowledge.[xvii]

According to this approach, sin is appropriately seen as a communication breakdown between the Creator and His creation. What’s more, we can sense this communication breakdown amongst ourselves, even though we are able to communicate and transfer information to a high degree. It’s fascinating to ponder how much more accurately we could communicate with God and ourselves without such a distorting effect.

An interesting notion revolving around the transcendence of information and Dembski’s understanding of divine action is that the universe is “informationally” open. Dembski argues that indeterministic models of the universe, through quantum mechanics, provide the possibility for “divine action [to] impart information into matter without disrupting ordinary physical causality.”[xviii]

Synopsis of Domning and Hellwig’s Original Selfishness

Domning and Hellwig take the position that Genesis 1–3 ought not to be understood as historical but rather as parables that reflect an inner moral struggle appropriate to humans once a certain level of consciousness is ascertained.[xix] Hellwig, in a chapter devoted to the historical and theological background of original sin, argues that throughout much of Christian history in the West, there has been a literal understanding of Genesis 3. However, she argues that with advances in biblical scholarship, this has significantly changed. The historicity of the narrative has been challenged, as she states: “given that the original authors do not seem to have intended the narrative in a literal sense”.[xx] Hellwig makes explicit that her concern is not with “‘the sin of Adam’ or [that] original sin [should] refer to one specific action at the beginning but rather to cumulative distortion.”[xxi] So Hellwig sees moral evil as a cultural transmission as opposed to a biological one as envisioned by Augustine through the physical act of procreation.[xxii]

The major components of the notion behind “original selfishness” include that the world is autonomous and free of divine compulsion. The fundamental source of natural evil lies in the fact that the universe is comprised of matter, which can be broken and lead to both pain and suffering. Once life emerges, natural selection takes over, preserving organisms with favourable traits that are adaptable to the environments at hand. All organisms are selfish, not in a pejorative sense but merely because of their propensity to survive.[xxiii] This inherent selfishness, which Domning calls “original selfishness,” is a substitute for what is typically referred to as “original sin.”[xxiv] All organisms share this original selfishness, from the origin of life to all present organisms, including humans. The difference with humans is that we have a moral consciousness to choose evil through free will, whereby guilt can result. Moral evil, although largely passed on through cultural transmission from sinful societies, is not the root. This is not the result of a pre-historical fall, so eventually moral evil evolves out of physical evil. However, perfect unselfishness cannot come from natural processes; we need supernatural grace to transcend our original selfishness through Christ’s salvation.[xxv] Having now outlined each of the positions, let us now put them into dialogue.

Creation and Evolution

Creation ex nihilo

Domning and Dembski agree on a non-static universe.[xxvi] Dembski affirms creation ex nihilo; he views God as the cause of the universe, bringing all of physical reality into being a finite time ago, as scientifically explained through the Standard Big Bang Model.[xxvii] It is worth pointing out, as a matter of clarification, that God acts as an ontologically prior cause, not a temporally prior cause, since time comes into being at the moment of creation.[xxviii] Although Domning does not explicitly affirm creation ex nihilo, given his view of a dynamic universe where material evolutionary processes have gradually led to the existence of morally reflective agents such as ourselves, it seems he would do so. Otherwise, he is left with the dilemma of a universe with an eternal past, which inevitably leads to the impossibility of traversing the infinite; simply put, it would be akin to jumping out of a bottomless pit, and this, in my view, would render evolution impossible since it cannot take off in the first place.[xxix] Moreover, evolution also assumes that the laws, initial conditions, and constants of physics need to be finely tuned to permit the emergence of matter, life, and consciousness. This is something worth pointing out, although neither author discusses it in great detail but simply takes it for granted.

Biological Evolution

When it comes to biological evolution, Domning has an extremely strong adherence to Neo-Darwinism, which, in addition to common descent, comprises the conjoining of the mechanisms of natural selection and random mutation. Domning suggests that evolution by natural selection and random mutation is not only the best but also the most plausible and logical way to explain common descent.[xxx] He allows for the potential of extended synthesis, but only in a minor way. The mechanism of natural selection is at the very core of his idea of “original selfishness.” Although natural selection seems to be one of the most highly plausible and empirically verified naturalistic mechanisms to explain the preservation of favourable species and traits through adaptation, new scientific findings could potentially undermine the explanatory scope and power to the extent that natural selection can explain common descent. We must always be reminded that science is provisional. If this were to happen, it would render Domning’s whole notion of “original selfishness” untenable or at the very least improbable unless he could find another explanation for “original selfishness” other than natural selection. His position is rather gutsy, as he emphatically states:

I am confident that the essentials of the argument I present here are based not on tentative details but on the most robust conclusions of evolutionary science… Darwinian evolution is here to stay.[xxxi]

Nonetheless, the veracity of these claims will surely be vindicated, discarded, or somehow augmented in the coming years.

Dembski, on the other hand, does not build his theodicy around one view of biological origins. His theodicy does possess one constraint that Domning’s view does not have. In order for Dembski’s theodicy to be compatible with evolution, he suggests that “God must not merely introduce existing human-like beings from outside the Garden [of Eden]. God must transform their consciousness so that they become rational moral agents made in God’s image.”[xxxii] This is essential to Dembski’s interpretation of Genesis 1–3. The significance of this consciousness being only transformed within the Garden is that if they underwent this transformation outside of Eden, it would expose humans to natural evils that they were not yet responsible for. Interestingly, Dembski also suggests that these first humans underwent a sort of “amnesia of their former animal life: operating on a higher plane of consciousness once infused with the breath of life, they would transcend the lower plane of consciousness on which they had previously operated—though, after the Fall, they might be tempted to resort to the lower consciousness.”[xxxiii] This view seems to imply that God is a deceiver of sorts by not allowing them to be aware of natural evil during this brief episode within the Garden of Eden. Nevertheless, his theodicy is compatible with special creationist models, although he reveals some deep scientific problems in both geology and cosmology with young earth creationism[xxxiv] and theological issues with old earth creationism.[xxxv] However, most importantly and relevant to our discussion is its compatibility with a number of theistic evolutionary positions, including ones that entail full-blown Neo-Darwinism. This malleability makes Dembski’s theodicy appear to be more vigorous than Domning’s “original selfishness.” This, I would argue, is a testimony to the strength of Dembski’s theodicy since it can encompass several different views as opposed to one stringent one. However, one could make the case that, in this respect, Dembski’s theodicy is neither falsifiable nor testable, but I’m not sure if that would miss the point since it is not a scientific theory. Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that it is extremely difficult to falsify scientific theories since they are quite malleable and adaptable to future developments. This point has been well demonstrated by philosopher Imre Lakatos.[xxxvi] Another way of examining scientific theories, especially ones that rely on historical evidence or are not strictly “scientific,” is through abductive reasoning, or what is known as making an inference to the best explanation.[xxxvii] Although Dembski seeks to preserve scientific orthodoxy regarding the age of the earth and theological orthodoxy regarding the Fall,[xxxviii] he admits he is looking towards metaphysics over science.

Monogenism versus polygenism

Domning indeed favours polygenism, which posits that the human race descended from a pool of early human couples.[xxxix] Domning devotes a chapter to refuting monogenism. He makes the point that, although it is not impossible for a population of our present size to have descended from a single couple, it is highly unlikely given our knowledge of paleontology and genetics.[xl] Domning suggests that evolution generally proceeds in breeding populations that are significantly larger than two.[xli] Genetically, our current population is of such variety that it would not likely be the result of a single human couple.[xlii] Domning relies much of his evidence on the findings and summaries of the eminent evolutionary geneticist, Francisco Ayala. This includes Ayala’s summaries regarding the segment of human DNA known as the DRB1 gene and the mitochondrial DNA.[xliii]

Domning takes the following position regarding monogenism: “[it] is not scientifically tenable, and it should no longer be relied on as a presupposition for theology, or accepted as a valid inference from other theological propositions.”[xliv] Similarly, the physicist Karl Giberson rejects the theodicy Dembski proposes since he regards God “choosing” a couple from a group of evolving “humans” by giving them His image and then placing them in Eden as highly implausible and unsatisfactory. He goes on to suggest that the writer of Genesis did not have this in mind.[xlv] Giberson’s view is certainly in line with Domning’s. Nonetheless, Dembski argues for the compatibility of his theodicy with polygenism, as he states:

What it does require is that a group of hominids, however many, had their loyalty to God fairly tested (fairness requiring a segregated area that gives no evidence of natural evil – the Garden); moreover, on taking the test, they all failed.[xlvi]

Dembski contends that his theodicy is “both satisfactory and natural” if “one is serious about preserving the Fall.”[xlvii] However, Dembski never explains how monogenist or polygenist accounts could potentially be compatible with the Fall.

Recently, an interesting position, although admittedly highly speculative, has emerged from two Catholic thinkers, Mike Flynn[xlviii] and philosopher Kenneth Kemp who demonstrate that there is no contradiction between a monogenist theological account of human origins and modern genetics and evolutionary biology.[xlix] What is important is a distinction between what it means to be human in a metaphysical sense and in a genetic and physiological sense. Briefly, they argue that God could have infused souls or higher consciousness into one of the thousands of couples, representing “Adam and Eve.” The descendants of this couple, infused with souls, mated with other couples that did not have souls. Eventually, the population of humans all had higher consciousness because of this interbreeding, and the ones without these souls eventually died off. Thus, consequently, no contradiction is apparent in the claim that every modern human is descended from a population of perhaps several thousand and one original couple. This is because humans who have descended from this “original” couple do not require the reception of all their genes from them.[l]

Nature’s Constancy

Dembski adheres to the constancy of nature but does not hold a view that the universe is closed to divine action. He argues that when God performs miracles such as raising Jesus from the dead, he is not violating natural law. Much in the same way that human laws do not cover every possible type of situation that may arise in society, the laws of nature do not cover everything that may arise in physical reality, suggesting that they are incomplete. God could work with or around them. Moreover, in response to those who negate the constancy of nature, Dembski illustrates the fact that it could potentially undermine the resurrection of Jesus. If Jesus’ resurrection is not a singular event caused by God, it could be something that is occurring in nature spontaneously that could cause people to rise from the dead. So, to deny nature’s constancy would disfavour the Christian believer. Dembski suggests that “divine activity may help nature accomplish things that, left to her own devices, nature never could; but divine activity does not change the nature of nature.”[li] Domning agrees with Dembski over nature’s constancy but would disagree with Dembski’s overall position since it seems to deny the autonomy and self-sufficiency of nature, which is crucial to Domning’s “original selfishness.” What is not clear is how he views God’s actions in nature. In the next section, we will look at his views on the problem of evil, where he aligns himself with Teilhard de Chardin. If his views align too closely with Teilhard’s, there are some foreseeable problems that can arise. Teilhard artificially rules out God’s intervention and insists that God can only create through evolution. Moreover, Teilhard limits God’s providence by following a deterministic view of physics (entailing a closed universe) without real justification. The science of quantum mechanics was already in existence during Teilhard’s productive years. A view from quantum mechanics would not support a neatly fashioned deterministic biosphere as Teilhard envisioned. Although Domning does not explicitly follow a deterministic depiction of the universe, he nonetheless aligns himself with some of Teilhard’s imposed limitations on God, as we shall see in the following section.

THE PROBLEM OF EVIL & ORIGINAL SIN

Moral Evil & Original Sin

Hellwig suggests that one cannot affirm the origin of evil through the Genesis 3 narrative.[lii] Dembski agrees that although the origin of evil cannot be affirmed by the narrative, he nonetheless attributes the sin of pride to Adam and Eve, which acts as a retroactive cause of the history of physical evil and suffering. As was explored earlier, Dembski views these first humans as gatekeepers who allow sin to pass through into the created order. Yet, the sin of pride is something that seems to be neglected in Domning and Hellwig’s proposition. One need not take a literal interpretation of Genesis to see that this sin transcends the purview of just selfishness and the inherent survival capacities of organisms. There is something within human nature that alienates us from God, and the mother of all sins is this desire to want something that is not intrinsically ours, to do things our way, as if they are above God’s ways. This is akin to denying God’s nature as God. This entertains the grandiose ambition of replacing God. Dembski notes that “the heart of evil is pride,” just as Eve thought she knew better than God “what was best for her.” [liii]

Nevertheless, Domning proposes a novel way of avoiding a Pelagian view that would start humans with a clean slate regarding sin. He suggests one where humans are “handicapped by inheritance: the inheritance of a proneness to sin.”[liv] Domning explains that his view of “original sin” functions in a way that, on one level, “original selfishness” is passed on genetically and phenotypically through all organisms, and on the second level, it is an inherited inclination to commit sin, which is only applicable to humans.[lv]

Both Dembski and Domning agree that humans possess free will. Moreover, reflective moral agents with free will are capable of sinning because of their moral knowledge and responsibility. They also agree that moral evil is ultimately explicable by human action and traceable to the original human or humans that first had the capacity to sin. However, baptism under Domning’s view, unlike an Augustinian interpretation, is not seen as removing “original sin” but as providing grace to transcend our “original selfishness.”

Natural (Physical) Evil

Domning follows Teilhard’s thought with respect to explaining natural evil. Teilhard and Domning believe that God can only create through evolution, as if it were the only logical possibility. Consequently, the argument follows that because of evolution and material reality, physical evil is an inevitable consequence. I would agree that this is certainly the case in the autonomous scenario presented by Domning.[lvi] Dembski, on the other hand, does not affirm an autonomous world, as he sees evil entering the world retroactively as caused by humanity’s “original sin,” which led to the Fall. Domning draws on Teilhard, who, in his work, Christianity and Evolution, asserts that:

In the earlier conception, God could create, (1) instantaneously, (2) isolated beings, (3) as often as he pleased. We are now beginning to see that creation can have only one object: a universe; that (observed ab intra) creation can be effected only by an evolutive process (of personalizing synthesis); and that it can come into action only once: when ‘absolute’ multiple (which is produced by antithesis to Trinitarian unity) is reduced, nothing is left to be united either in God or ‘outside’ God. The recognition that ‘God cannot create except evolutively’ provides a radical solution for our reason to the problem of evil (which is a direct ‘effect’ of evolution), and at the same time explains the manifest and mysterious association of matter and spirit.[lvii]

Teilhard criticizes earlier conceptions of direct interventionist creation as envisioned in young and old earth creationism. He, however, despite his claim, does not provide a satisfactory solution to the problem of evil since the problem remains regardless of the process by which God chooses to create. Teilhard also does not substantiate his claim that God can create only through evolution. Why limit a sovereign God in such a way? Indeed, Domning must answer the very same question. Domning clearly states, with respect to God creating in an alternative fashion:

Is the gain worth the pain? Not if there was an easier way to do the job; but the alternative is an illusion… When we confront suffering and death, therefore, we can take some comfort in knowing that God is not incompetent or callous, but that there was simply no other way to make the sort of world God evidently wanted. [lviii]

Even if God were to solely create through evolution, it does not mean he could not do otherwise, and there is no reason to think that he could still not be intimately involved in the process, perhaps acting at the quantum level, leaving such an involvement perhaps ambiguous.

The essential point here is that whether God creates through direct intervention or indirectly through Darwinian mechanisms, the problem remains. God is still responsible since He is the source of all being. Dembski explains this point succinctly when he states, “Creation entails responsibility. The buck always stops with the Creator. That’s why so much of contemporary theology has a problem not just with God intervening in nature but also with the traditional doctrine of creation ex nihilo, which makes God the source of nature.”[lix] Thus, one is puzzled when Domning suggests that, in light of evolution, the problem of physical evil is a “pseudoproblem.”[lx]

It is difficult to say whether Dembski’s theodicy of putting the blame on human sin for the cause of natural evil retroactively is preferable to Domning’s autonomous universe. Either way, God is ultimately responsible for physical evil, although one shifts the blame to nature’s autonomy and the other to human decision-making. Moreover, each respective thinker considers this world to be the best possible world that God could have created. Nevertheless, the question remains as to which is the more plausible of the two.[lxi]

Interpreting Genesis 1-3 and Related Themes

Beyond Biblical Literalism: A Non-Historical Reading?

As we have already seen, Domning affirms polgyenism, which undermines the historicity of a literal Adam and Eve. Domning puts himself starkly against Dembski’s accommodation to reconcile monogenist or even polygenist views with a somewhat historical understanding of Adam and Eve (or the original humans), arguing that hybrid views are based on misunderstandings of the findings of evolution. Domning states that:

Some Catholic writers compartmentalize their thinking to the extent of accepting geological time, evolution, and even human evolution, while simultaneously retaining belief in a literal Adam, Eve, and Garden of Eden. But such a hybrid view (reflecting the persistent influence of Humani Generis but also older than that) depends on an untenably superficial understanding of evolution and its pervasive theological implications.[lxii]

Despite Domning’s claims, I provided an example, as a thought experiment, of a logically possible account for our understanding of genetics and evolutionary biology with a monogenist view of human origins, as argued by Flynn and Kemp.

A Common Desire for Affirming a Concrete Historical Past

Both Domning and Dembski want to understand a concrete historical past with respect to a traceable “original sin” of some sort, whether via mechanism or agency. Hellwig leaves the understanding of origins to Domning and other scientists. Hellwig refuses to acknowledge a traceable beginning for sin by suggesting: “the real exigence is to clarify the situation of the here and now, any here and now, as a task for human living.”[lxiii]

The Purpose of the Doctrine of Original Sin

Hellwig argues that the purpose of the Christian doctrine of original sin in theology is three-pronged: 1) raises awareness of suffering and evil—to be critiqued as to their causes and to be resisted; 2) evil is not just outside of oneself but one can find it internally by looking at one’s own conduct, relationships, and values; and 3) the Creator is greater than all creaturely actions, making redemption possible from sin and suffering.[lxiv] Dembski certainly agrees with Hellwig’s three points; however, he does not believe he needs to go outside the Genesis 1–3 narrative to answer a historically traceable explanation for “original sin.” Dembski takes Hellwig’s first point to a stronger realization than just awareness but to the depths of the gravity of sin as caused by the human will.[lxv] Dembski asks the question, “Why would a benevolent God allow natural evil to afflict an otherwise innocent nature in response to human moral evil?”[lxvi] Dembski responds to this question by suggesting that:

We can say that it is to manifest the full consequences of human sin so that when Christ redeems us, we may clearly understand what we have been redeemed from. Without this clarity about the evil we have set in motion, we will always be in danger of reverting back to it because we do not see its gravity. Instead, we will treat it lightly, rationalize it, shift the blame for it – in short, we will do anything but face the tragedy of willfully separating ourselves from the source of our life, who is God.[lxvii]

Crucial to Dembski’s theodicy is a historical Fall where humanity’s original sin affects the totality of nature, past, present, and future. On the other hand, Domning and Hellwig see Eden as an etiological myth, as “an ancient attempt to explain how we got in our present fix.”[lxviii] Yet, as Domning indicates, he wants historical concreteness, not just etiological myths.[lxix] Moreover, he wants a metaphysics that not only assures a hopeful future but also “understands an actual past.”[lxx] Although his understanding of scripture is distinct, his goal in this respect is similar to Dembski’s. Where it does differ is on epistemology Domning wants a new account of origins based on scientific data[lxxi] whereas Dembski has been clear that his project is metaphysical.

Retroactive Effects of the Fall & a Kairological Reading of Genesis 1-3

One of the major difficulties Dembski faces is explaining retroactivity, or “backward causation,” since it seems completely counterintuitive. Domning intimates that such a view that Dembski proposes is untenable when he states:

This much we know for certain, if cause precedes effect: whoever or whatever he is taken to be, the Adam of the Fall was not responsible for introducing physical suffering and death into the order of nature. Nor, as shown above, can poor Adam be blamed for all the forms of mayhem that we humans inflict on each other; those were well established among evolving organisms long before his and our advent.[lxxii]

A response to such a view is what Dembski labours rigorously to explain throughout his book. Dembski argues that both scripture and Christian experience support a view of divine action that encompasses God acting retroactively. In scriptural support, he lists Isaiah 46:9–10 and 65:24, whereby God says, “It shall come to pass, that before they call, I will answer; and while they are yet speaking, I will hear.” In terms of experience, God allows for our prayers to possibly affect things retroactively since He is not bound by space and time. How is this possible, though?

Newcomb’s Paradox can help illustrate this, which shows how events that occur in the present can materially affect the past.[lxxiii] Dembski also goes beyond Newcomb’s Paradox, taking into account chaos theory, since in the world there are no causally isolated events, so the minutest event affects the entire created order. Taking this into consideration, alongside what it means for God to act to anticipate future events, is what Dembski calls the “infinite dialectic.”[lxxiv] Here, God acts like the cause of all causes, acting upon creation at all times and places.[lxxv]

Admittedly, a rather strange move is made by Dembski in his approach to reading Genesis 1–3 in what he calls a kairological way. To understand this Kairological reading, one must understand that God acts transtemporally across time.[lxxvi] The distinction between Chronos and Kairos is important to understand. Chronos denotes mere duration in physical time, whereas Kairos denotes time through the vantage point of God’s purposes subject to invisible realms. What makes this an awkward reading is that he is imposing New Testament descriptors to explain how he perceives God’s divine action in Genesis—something foreign to the language designated by the authors of Genesis. Nonetheless, in such an approach, God is purported to respond to the Fall not simply after it but before it, but how?

Dembski makes a further distinction between two logics of creation: 1) causal temporal logic (bottom-up view) and 2) intentional-semantic logic (top-down view) from the vantage point of divine purpose and action.[lxxvii] Dembski elucidates the distinction by suggesting intentional semantic logic treats time as nonlinear. Neither logic contradicts the other since

The intentional-semantic logic is ontologically prior to the causal temporal logic.[lxxviii] God has always existed and acted on the basis of intentions and meanings. The world, by contrast has a beginning and end. It operates according to the causal-temporal logic because God, in an intentional act, created it that way. Divine action is therefore a more fundamental mode of causation than physical causation.[lxxix]

Genesis 1 is not to be interpreted as chronological time (chronos), but kairological time through the perspective of God’s purposes (kairos).[lxxx] In other words, they are episodes in God’s mind that are transposed through His creative action into the world. Furthermore, the kairological interpretation of the six days is anthropocentric, as Genesis clearly indicates that humanity is the end of creation.[lxxxi] Dembski argues that the knowledge of our humanity provides us insight into the Godhead for three reasons: 1) Humans are the end of creation; 2) humans are made in the image of God; and 3) the incarnation of the second person of the Trinity as a human being are valid points for understanding God.[lxxxii] The fall represents the entry of evil, which distorts and deforms the created order. God’s response is to do damage control and ultimately respond through the cross and the second coming of Christ.[lxxxiii] God wills all the natural evil that predates humanity on purpose.[lxxxiv]

One may still wonder how the prior causal linkage between moral evil and natural evil is preferable to an autonomous evolutionary view to defend God’s justice. I can’t necessarily see why one is preferable over the other, given the fact that God is ultimately responsible for either explanation.[lxxxv]

Dembski also argues for three wills of God in Genesis 3:17–18, including: 1) an active will—to bring a desired event—the call of Abraham (Gen. 12); 2) a providential will—seasonal weather patterns (Gen. 8:22); and 3) a permissive will—God permitting Satan to test Job (Job 1 and 2). Dembski’s theodicy is compatible with a literal Adam and Eve, but it is not necessary (as was mentioned above, many human couples could coexist simultaneously that bore the image of God).[lxxxvi] Dembski justifies the linkage between moral evil and natural evil by making reference to Paul (Romans 8:20–22) and early church fathers such as John Chrysostom.[lxxxvii]

Concluding Reflections

Dembski demonstrates no direct knowledge of Domning and Hellwig’s work, even though his book was published three years later. The closest Dembski comes to engaging with the concept of “original selfishness” is seen in response to Karl Giberson’s reference to his ideas of evolution being driven by selfishness found in his book Saving Darwin.[lxxxviii]

Ultimately, both Domning and Hellwig’s[lxxxix] and Dembski’s[xc] positions demonstrate a consonance between the Book of Nature and the Book of Revelation (Scripture). The evidence before them is precisely the same. God’s permissive will cannot eliminate His responsibility for natural evil. Dembski’s theodicy segregates humanity from natural evil in the Garden until they possess the image of God and commit original sin, whereas on Domning’s “original selfishness” view, humanity undergoes natural evil through a gradual emergence of consciousness, which leads to their moral aptitude. The question must be asked: when precisely does this moment of moral reflection arrive? Is it really so gradual or is it sudden? The gradualness of the evolution of moral reflection seems to pose a severe conflict with Dembski’s segregated garden: at what point does one decide they are not culpable for experiencing natural evil, as opposed to being almost there but not quite yet still experiencing natural evil?

What differs is their epistemological approach. The question before us is: which position coheres better with the scientific, philosophical, theological, and biblical evidence available? And what is a better explanation: sin being the result of our evolutionary history or the cause of it? I would argue that both positions are internally consistent once you accept certain assumptions. In the case of Domning and Hellwig, you must accept the Neo-Darwinian mechanisms to explain common descent and a non-historical interpretation of Genesis 1–3. In Dembski’s case, you can accept a number of differing evolutionary accounts, so if Neo-Darwinism is discarded or significantly augmented in the future, it does not threaten his theodicy. However, one must presuppose that an actual historical Fall took place. I can only suggest that further research and thought on this subject can give us any hope of advancing this dialogue. I would argue that the greatest strength of Domning and Hellwig’s view is this notion of an inherent selfishness that still remains within us and has been part of our evolutionary history. It coincides with the vast number of evils we find in nature that are shockingly similar to our own behaviours. It seems not only empirically but intuitively true. However, if we take a lesson from modern science, perhaps intuition is not the most reliable avenue to pursue in order to understand the nature of reality. The appeal of Dembski’s theodicy is its malleability and his deep efforts to be faithful to both contemporary scientific findings and the traditional western understanding of “original sin.”

One of the major strengths of Domning and Hellwig’s work is the combination of their respective expertise in evolutionary biology and theology. Dembski’s strength lies in his proposition of the utilisation of the concept of information for divine action and his innovative trinitarian mode of creation. Indeed, Dembski’s insights explored in this work and others, including his latest work Being as Communion: A Metaphysics of Information, show that he makes a significant contribution to the relationship between divine action and information. I would tentatively suggest that much of Dembski’s innovative thought revolving around the notion of information will play a fundamental role in not only giving us a better understanding of God’s divine action as understood throughout nature but can also potentially help create a deep consonance with evolutionary biology. On the other hand, Domning lacks any such methodology and relies on the mere autonomy of nature, which could create difficulties in singular events such as the fine tuning of the laws of physics and the origin of life.

Nonetheless, there is an interesting interconnection with Dembski’s notion of the applicability of communication theory in relation to God’s relationship with creation in lieu of the distorting effects of the Fall. This can be seen through the transmission of God’s message to humanity’s reception of it via the so-called “noise source” and with the gradual distortion envisioned in Domning and Hellwig’s evolutionary theological position with respect to the development of original selfishness, which is ubiquitous throughout life. Perhaps further research will reveal a deeper interconnection between these two notions. However, both examples need God’s intervention for eternal salvation.

I believe that both positions can have a tremendous impact on Christians who are having extreme difficulty reconciling their beliefs regarding evolution, particularly common descent, as explained via Darwinian mechanisms and the salvific gospel message. Any of these positions provides a more plausible and robust understanding of sin, evil, and the fall than standard special creationist views such as Young Earth Creationism and Old Earth Creationism. Either way, the message of salvation is not lost. All of the authors agree on the power of the cross and the promise of everlasting life as first instantiated by the resurrection of Christ. Domning sees Christ saving us from our evolutionary history and transcending beyond “original selfishness.” This can only be accomplished by transcending the animal kingdom’s reciprocal form of altruism to Jesus’ radical message of perfect altruism, where we are called to love not only our neighbours as ourselves but also our enemies and those who persecute us. Not only Jesus’ message but also his example and self-sacrifice on the cross can save us from our sinful and fallen natures. Dembski concurs on the radical nature of Jesus’ teaching and action when he puts an emphasis on Jesus’ humility, especially when he compares his example to some of the great thinkers of western history, including Aristotle:

Among the vast catalogue of virtues that adorn Aristotle’s ethics, humility is nowhere to be found. Yet, humility is the only virtue that captures the love of God for humanity, a love fully expressed in the Cross. Only by humility does Christ – and those who share his life – defeat the sin of pride that led to the Fall.[xci]

Dembski also notes that an infinite God effectively reduces himself to zero by dying in his human nature on the cross;[xcii] this is the ultimate example of perfect altruism to destroy our sinful ways. The beauty of salvation infinitely transcends the gravity of sin. This is to show that what is of central importance is how we can get out of the predicament of sin, more so than the historical account of how sin came into the world. Even though we have two creative, although quite distinct, accounts of how such a thing could have occurred in space-time.

Just as there have been multiple theories of atonement throughout church history, some were debated and rejected while others remained to be studied and preached.[xciii] The totality of Christ’s atoning sacrifice cannot be encompassed or reduced to a single theory. Indeed, we find a number of images to illustrate Christ’s work.[xciv] A prudent and fruitful approach is taken by the physicist and religion-science author, Loren Haarsma, when he suggests that:

If the problem of sin is so vast that it requires such an astonishing solution as the Atonement, perhaps we will also need multiple theories of original sin. Some theories of will be discarded as being inconsistent with God’s revelation in scripture. Those that remain should deepen our understanding and our appreciation of God’s grace and the immensity of the rescue God undertook through Jesus Christ.[xcv]

Much in the same way, the complexities surrounding the intersection of evolution, sin, evil, and the Fall will involve much debate. Some models attempting to make sense of all these points of intersection will be rejected, while more fruitful ones may remain for further examination and reflection. It seems as though, based on this analysis, both Dembski’s theodicy and Domning and Hellwig’s “original selfishness” will endure such a test for the foreseeable future.

Caption: Claude Shannon’s communication model; a schematic diagram of a general communication system (See figure 1 below).[xcvi]

[i] William Dembski possesses a PhD in mathematics and philosophy, both from the University of Chicago. He also has a M. Div. in theology. He is a leading thinker of the Intelligent Design (ID) program. Although this work is of interest to ID, it can also operate separately from those views.

[ii] Daryl Domning is a respected paleontologist. He has authored numerous scientific papers. He has also contributed a number of papers related to the science-religion interaction. He is also a devout Roman Catholic.

[iii] Hellwig died before the publication of this book. She was an academic nun who possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of Catholicism. She was also a well-published and respected academic theologian.

[iv] See Gerald Rau, Mapping the Origins Debate: Six Models of the Beginning of Everything (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012). Theistic evolution may encompass three of the following possibilities, whether through Darwinian mechanisms and/or others: Non-teleological: The Creator does not interfere with natural causation after the point of creation and has no specific goals for creation. Planned evolution: The Creator formed the creation such that no intervention was necessary after creation to bring about his goals. Directed Evolution: The Creator is still active in His creation through secondary causes in order to bring about His intended goals.

[v] William A. Dembski, The End of Christianity: Finding a Good God in an Evil World (Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Publishing Group, 2009), 8.

[vi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 8.

[vii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 8.

[viii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 9.

[ix] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 9.

[x] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 9. This has been traditionally understood as the serpent’s doing in Genesis 3.

[xi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 10.

[xii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 10.

[xiii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 86.

[xiv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 87.

[xv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 87.

[xvi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 87.

[xvii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 104.

[xviii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 117.

[xix] Daryl P. Domning and Monika K. Hellwig, Original Selfishness: Original Sin and Evil in the Light of Evolution (Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2006), 4.

[xx] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 15.

[xxi] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 16.

[xxii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 13.

[xxiii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 184.

[xxiv] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 184.

[xxv] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 184.

[xxvi] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 83; Dembski, The End of Christianity, 65.

[xxvii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 64-65.

[xxviii] The work of William Lane Craig explains, using Immanuel Kant’s example, that cause and effect can occur simultaneously, through the compression of a heavy metal ball on a couch, the ball causing the compression and the compression itself are simultaneous. See William Lane Craig and Quentin Smith, Theism, Atheism, and Big Bang Cosmology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

[xxix] I presented a paper at the Aristotle & the Peripatetic Tradition conference on October 16 and 17, 2014, at the Dominican University College in Ottawa, Canada, on this very subject, arguing specifically that consciousness cannot emerge in an eternal universe. The paper is titled “Philoponus contra Aristotle: The Impossibility of an Eternal Universe and the Emergence of Consciousness.” It awaits publication with Brill Publishers.

[xxx] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 37-40.

[xxxi] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 179.

[xxxii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 159.

[xxxiii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 155.

[xxxiv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 64-70

[xxxv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 78-81.

[xxxvi] See Imre Lakatos, The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. Philosophical Papers Vol. 1, ed. John Worrall and Gregory Currie (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978).

[xxxvii] Peter Lipton, Inference to the Best Explanation (New York: Routledge, 1991).

[xxxviii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 78.

[xxxix] It is important to note that before the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, a number of creationists, such as Louis Agassiz, held to a polygenist interpretation, which is now considered part of scientific racism. The current debates over monogenism and polygenism have transcended such racial motivations of 19th-century biologists.

[xl] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 71.

[xli] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 71.

[xlii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 71.

[xliii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 71-73.

[xliv] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 174.

[xlv] Karl Giberson, Saving Darwin: How to Be a Christian and Believe in Evolution (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2008), 12.

[xlvi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 146.

[xlvii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 162.

[xlviii] An exposition of Mike Flynn’s position can be found at this website, accessed April 28, 2015, http://tofspot.blogspot.ca/2011/09/adam-and-eve-and-ted-and-alice.html.

[xlix] Kenneth W. Kemp, “Science, Theology, and Monogenesis,” American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 85, No. 2, 2011: 217-236, accessed April 28, 2015, http://www3.nd.edu/~afreddos/papers/kemp-monogenism.pdf.

[l] Kemp, “Science, Theology, and Monogenesis,” American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 85, No. 2, 2011: 232.

[li] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 58.

[lii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 12.

[liii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 135.

[liv] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 146.

[lv] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 145.

[lvi] However, I don’t think anyone posits that material reality, at least as we know it, can exist without physical evil since things are obviously breakable and subject to pain and suffering. This is not a necessary realization exclusive to an evolutionary universe.

[lvii] Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Christianity and Evolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 179.

[lviii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 152.

[lix] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 163.

[lx] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 181.

[lxi] It could be worth considering, as another alternative, Domning’s “original selfishness” as a position that could still be applicable even to Dembski’s theodicy until the advent of moral agents, as long as these moral agents like “Adam and Even” were segregated at such a particular point in their evolution from natural evil that they were not yet “responsible” for. In a sense, the two can coincide, but whether the remnants of this “original selfishness” could be said to still affect them once they are expulsed from the Garden of Eden or if they become tainted by their sin of pride is a matter for further reflection.

[lxii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 20.

[lxiii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 98.

[lxiv] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 97.

[lxv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 43.

[lxvi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 43.

[lxvii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 45.

[lxviii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 147.

[lxix] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 146.

[lxx] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 46.

[lxxi] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 146.

[lxxii] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 139.

[lxxiii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 128.

[lxxiv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 140.

[lxxv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 140.

[lxxvi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 124.

[lxxvii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 133.

[lxxviii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 132.

[lxxix] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 132.

[lxxx] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 142.

[lxxxi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 143.

[lxxxii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 144.

[lxxxiii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 145.

[lxxxiv] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 146.

[lxxxv] The division may seem artificial, but both positions have their difficulties that need to be refined.

[lxxxvi] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 145-146.

[lxxxvii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 147.

[lxxxviii] Giberson, Saving Darwin, 162. Through perusing over the index and end notes of Giberson’s book, it seems not to have any direct acquaintance with Domning and Hellwig’s “Original Seflishness.”

[lxxxix] Domning and Hellwig, Original Selfishness, 1.

[xc] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 71.

[xci] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 22.

[xcii] Dembski, The End of Christianity, 22.

[xciii] Please see Peter Schmiechen, Saving Power: Theories of Atonement and Forms of the Church (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005).

[xciv] Loren Haarsma, “Why the Church Needs Multiple Theories of Original Sin” http://biologos.org/blog/why-the-church-needs-multiple-theories-of-original-sin#footnote-3 Last Accessed April 13, 2015.

[xcv] Loren Haarsma, “Why the Church Needs Multiple Theories of Original Sin” http://biologos.org/blog/why-the-church-needs-multiple-theories-of-original-sin#footnote-3 Last Accessed April 13, 2015.

[xcvi] Shannon’s communication diagram with the incorporation of Dembski’s Trinitarian Mode of Communication. Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication (Urbana, III.: University of Illinois Press, 1949), 34.

References

Craig, William Lane and Quentin Smith. Theism, Atheism, and Big Bang Cosmology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Dembski, William A. The End of Christianity: Finding a Good God in an Evil World. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Publishing Group, 2009.

Domning Daryl P. and Monika K. Hellwig. Original Selfishness: Original Sin and Evil in the Light of Evolution. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2006.

Flynn, Mike. http://tofspot.blogspot.ca/2011/09/adam-and-eve-and-ted-and-alice.html accessed April 28, 2015.

Giberson, Karl. Saving Darwin: How to Be a Christian and Believe in Evolution. San Francisco: HarperOne, 2008.

Haarsma, Loren. “Why the Church Needs Multiple Theories of Original Sin” http://biologos.org/blog/why-the-church-needs-multiple-theories-of-original-sin#footnote-3 Last Accessed April 13, 2015.

Kemp, Kenneth W. “Science, Theology, and Monogenesis,” American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 85, No. 2, 2011: 217-236, accessed April 28, 2015, http://www3.nd.edu/~afreddos/papers/kemp-monogenism.pdf

Lakatos, Imre. The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. Philosophical Papers Vol. 1, ed. John Worrall and Gregory Currie. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Lipton, Peter. Inference to the Best Explanation. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Rau, Gerald. Mapping the Origins Debate: Six Models of the Beginning of Everything. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012.

Schmiechen, Peter. Saving Power: Theories of Atonement and Forms of the Church. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005.

Shannon, Claude and Warren Weaver. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, III.: University of Illinois Press, 1949.

Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. Christianity and Evolution. New York: Harper & Row, 1965.