He Who Wrestles With God in Public: Jordan Peterson Versus Himself

Peterson, who has notoriously stood aloof from formal religion, found out that mere psycho-spirituality couldn't stand up to committed opposition to God.

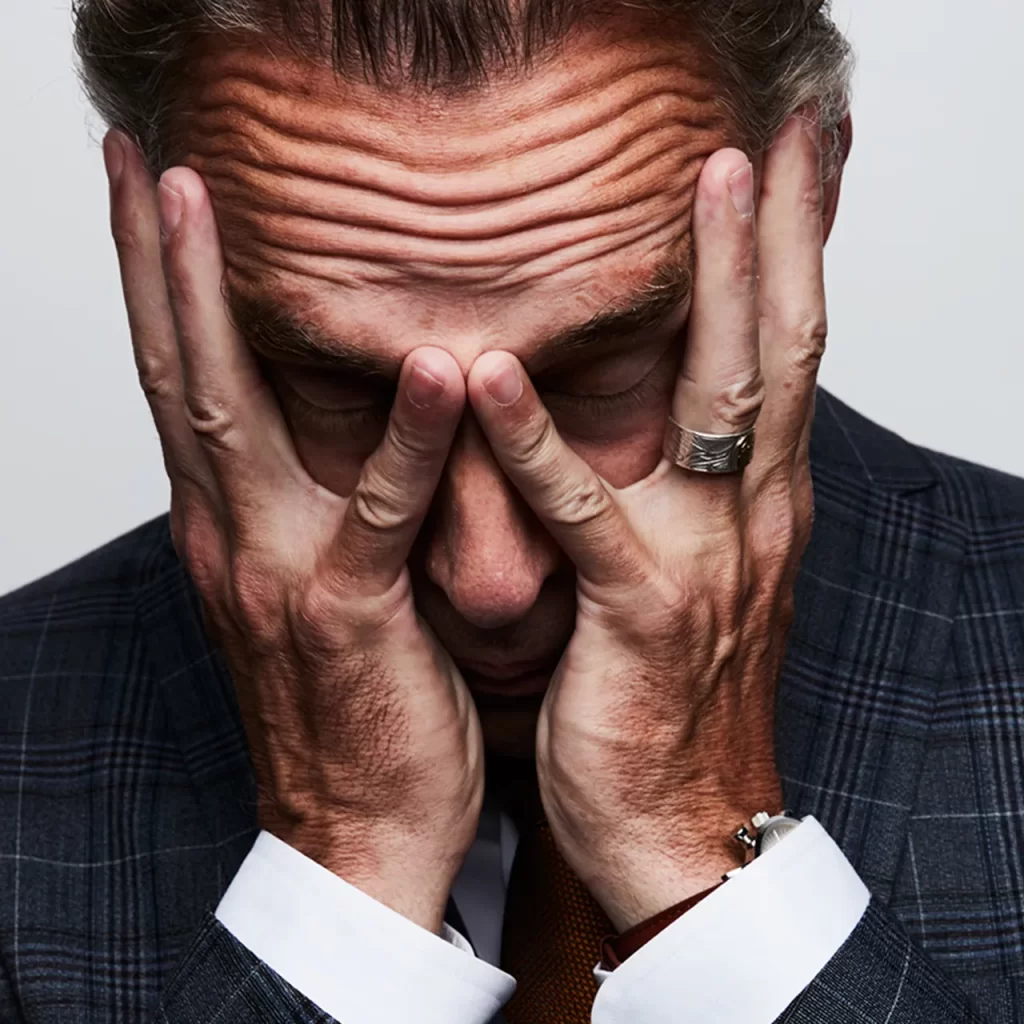

Jordan Peterson’s recent appearance on Jubilee’s viral YouTube debate wasn’t just another skirmish in the culture war between belief and unbelief. It revealed something deeper and more unsettling: the ongoing drama of a man caught between archetype and the Incarnation, between myth and metaphysical truth. The event was less about the twenty atheists who challenged him and more about the unresolved questions that have long surrounded Peterson’s theology or lack thereof.

For years, observers have speculated: Is Peterson inching toward Christianity, or is he crafting a symbolic system and even inventing a mythic religion of his own? The Jubilee debate brought this tension into sharp focus. What unfolded wasn’t so much a theological dialogue but perhaps more of a public unravelling. The spectacle laid bare the limits of symbolic Christianity and raised a question that’s been simmering for nearly a decade: Can a man live as though Christianity were true without ever affirming that it is?

I’ll delve deep into the Jubilee debate not just as a cultural moment but as a revealing chapter in Peterson’s ongoing spiritual ambiguity. This essay delves into his now-notorious theological hesitation, the well-meaning generosity of some Christian philosophers, and the silent consequences of not crossing the boundary into genuine faith.

The Long Road of Ambiguity

Jordan Peterson has long stood, as I noted in earlier reflections, as a paradoxical figure in contemporary religious, cultural, political, and philosophical discourse. From his first book, Maps of Meaning, which explored the deep structures of belief, to televised debates on God and morality, for close to two decades Peterson has occupied a public role wrestling with meaning. But while his psychological insights are often compelling, his metaphysical commitments remain elusive.

Peterson consistently stops short of theological affirmation. His notion of the sacred is grounded in evolutionary utility and symbolic resonance, not in divine revelation. As I argued elsewhere, the real question is not whether God is a necessary archetype, but whether He has spoken and has revealed Himself in human history, most decisively in Jesus Christ. Until Peterson engages this question directly, he will remain suspended between symbol and sacrament, between Logos as archetype and Logos incarnate.

These concerns are not new for me. In my 2018 article, “The Peterson–Craig Encounter: A Missed Opportunity?,” I recognized Peterson’s cultural importance and psychological acumen, but also warned of a deep tension in his thought. Although affirming moral objectivity and rejecting relativism, Peterson does so inconsistently, lacking a clear referential grounding, i.e., God. This illustrates the insufficiency of naturalistic and pragmatic frameworks. He admitted a kind of Platonic realm and even referred to the transcendent as “irrational.” I called attention to his conflation of methodological with metaphysical naturalism, his epistemological confusion between pragmatic and objective truth, and his evasions when it came to the existence of God, the historicity of Jesus and the resurrection, and the coherence of Christian belief. Though he rescued many from nihilism, I concluded that his philosophical vision was not equipped to defend Christian theism.

The Jubilee Format: Hostile Parade

The Jubilee debate was billed as a clash between Peterson and twenty atheists. Like the earlier episode, “1 Atheist vs. 25 Christians,” which featured Alex O’Connor (Cosmic Skeptic), the format placed a single participant in the center, surrounded by rotating interlocutors. But while O’Connor’s debate was structured and relatively measured in tone, Peterson’s debate was far more adversarial and emotionally charged.

The most viral moment was not philosophical, but emotional:

“You’re really quite something, aren’t you?” Peterson snapped.

“Aren’t I?” Danny (one of the atheist debaters) replied. “But you’re really quite nothing, aren’t you? You’re not a Christian.”

This line reverberated across social media, spawning headlines and memes. For many, it exposed what they saw as Peterson’s bluff. For others, it symbolized an existential wound for both believers and non-believers.

Interpreting the Moment: Between Charity and Critique

Some Christian thinkers attempted to steelman Peterson’s approach. Trent Dougherty, in conversation with Cameron Bertuzzi of Capturing Christianity, suggested that Peterson’s claim, “everyone worships something,” could be framed as powerful evidence for theism within a Bayesian framework. If humans are universally religious, then theism better explains this data than atheism.

Christian philosopher William Lane Craig, in dialogue with Sean McDowell, also offered a more pastoral reading. He proposed that Peterson’s evasiveness might stem from being a “baby Christian,” someone in the early stages of belief. He cautioned against harsh judgment: “We don’t know his heart… but he’s certainly evasive—and I think that’s deliberate.”

Craig speculated that Peterson’s ambiguity is strategic: “If I were his publicity agent, I’d say be as evasive as you can. That evokes the mystery, promotes the controversy.” But Craig also invoked Luke 12:8–9, warning of the danger for professing Christians in denying Christ before others.

Generous though they are, such interpretations only serve to illuminate the core dilemma: the uneasy coexistence of archetype and the Incarnation, where symbolic truths, though not false, become theologically hollow when severed from the concrete reality of divine revelation.

Theological Evasiveness and Linguistic Obfuscation

As I clearly indicated in my 2024 essay “Why We Should Be Cautious of Jordan Peterson,” his theological evasiveness is not new. When asked whether he believes in God or affirms Christ, Peterson typically shifts into symbolic language:

- God becomes “the highest value.”

- Belief becomes “what we live out.”

- Conscience becomes God.

This strategy often functions more as conceptual sleight-of-hand than serious theology. As Matthew Whiteley rightly observed in “The Sad Demise of Jordan Peterson,” such rhetorical shifts now appear more like obfuscation than insight.

When Peterson’s pragmatism is put to the test, particularly his claim to “live as though Christianity were true,” it collapses under the weight of Paul’s warning: if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile (1 Corinthians 15:17).

Peterson has cited Cardinal Newman to support his view that “God is conscience,” but this is a clear misreading. Newman never equated conscience with God Himself. Instead, he saw conscience as the echo of God’s voice—not its source, and certainly not God. Peterson psychologizes what Newman theologizes.

Steelmanning Peterson: Worship as Evidence?

Despite the conceptual ambiguity of Peterson’s language, some Christian thinkers have attempted to reconstruct his claims in more rigorous philosophical terms. In a livestream hosted by Capturing Christianity, Trent Dougherty and Cameron Bertuzzi discuss a Bayesian argument based on Peterson’s assertion that “everyone worships something.” They proposed that the universal human tendency to worship, whether it is God, ideology, or the self, is far more probable if theism is true than if atheism is. Using modeling software, they showed how even one datum, i.e., ubiquitous worship, can significantly raise the probability of theism. While Peterson may not be reasoning this way explicitly, his focus on worship aligns with the idea that humans are naturally oriented toward ultimate meaning, a reality better explained by theism than by atheism.

The strength of this reconstruction lies more in the interpretive generosity of Peterson’s defenders than in the clarity of his own formulation. The debate revealed the weakness of his position when pressed: if everyone worships their highest value, then the term “atheist” becomes incoherent, and “God” is so abstract as to become functionally meaningless. Peterson’s symbolic framing, though provocative, lacks theological anchoring. Thus, while his instincts may align with theistic intuitions, his language ultimately dissolves the specificity required for genuine belief.

The Theological Dilemma: Christ or Conscience?

This is the crossroads Peterson continues to approach without crossing. He does not profess belief in the crucified and risen Christ. He gestures toward the moral structure of Christianity but shies away from its metaphysical center.

In the viral exchange with Danny, this evasion was not met with reflection but with irritation. It exposed what I earlier called the “limits of symbolic Christianity.” Archetypes are incapable of saving you. And conscience is not equivalent to grace.

In my article, “The Peterson–Craig Encounter: A Missed Opportunity,” I lamented Peterson’s unwillingness to engage Craig on God’s nature, the Incarnation, or the resurrection. That missed opportunity now seems somewhat prophetic. The Jubilee debate was the natural outgrowth of years of side-stepping core theological truths.

The question is not whether God functions as a helpful fiction, but whether He has revealed Himself definitively both historically and incarnationally.

Until Peterson confronts that question, his theological project remains incomplete.

In fact, in July 2018, I handed Peterson a printed letter in person, along with two of my writings: an academic article titled “The Deconstructing of Deconstructionism: Peterson Versus Derrida” and the other, “The Peterson–Craig Encounter: A Missed Opportunity?” In the letter, I commended his cultural influence and intellectual courage in confronting destructive ideologies, but urged him to move beyond figures like Sam Harris when grappling with questions about God. I encouraged him to engage the contemporary renaissance in Christian philosophy and the rigorous historical scholarship on the resurrection. My goal was not to criticize, but to invite him to wrestle more seriously with revealed truth. I made it clear that truth and love are not merely archetypal ideals but, if aimed at ultimacy, converge in a transcendent source. The letter was not a polemic but a plea, written in the hope that he might one day affirm not merely Christianity’s pragmatic truth, but its objective truth.

Moving Forward: Between Hope and Hesitation

Reactions to the Jubilee debate have varied widely. Some demand Peterson clarify his theological stance. Others argue he deserves space to wrestle with mystery. Both instincts are understandable. But what is often overlooked is Peterson’s symbolic role in this stage in the West’s moral reckoning.

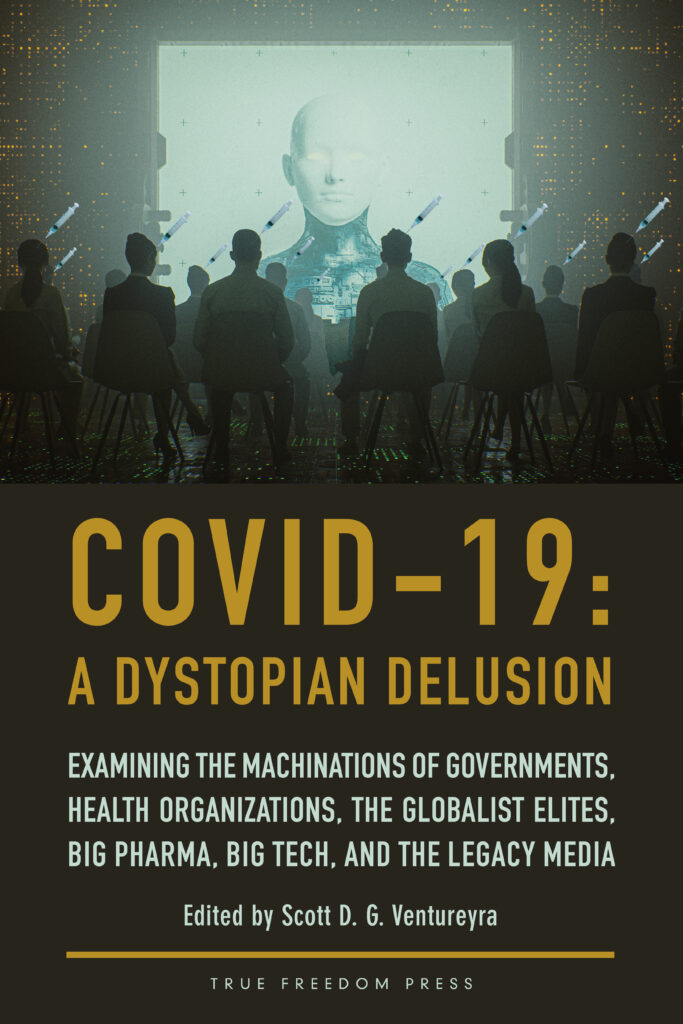

My 2024 article “Why We Should Be Cautious of Jordan Peterson” offered a more direct and severe assessment. There, I critiqued Peterson’s persistent ambiguity about the resurrection, his equivocation on truth, and his politicized pragmatism, which often disguises deeper theological indecision. He habitually reframes metaphysical claims in psychological or Darwinian terms, positioning himself between believer and skeptic to maintain broad appeal. His handling of the COVID crisis was emblematic. Despite his deep awareness of totalitarian regimes, Peterson urged followers to “suspend judgment” and “get the damn vaccine,” even requiring vaccination for his 2022 Freedom Tour. His later criticisms of mandates only emerged after the public tide had turned. This belated shift, coming after the damage was done, appeared less principled than opportunistic. In COVID-19: A Dystopian Delusion, I highlighted similar patterns among public intellectuals who failed to speak when it mattered most. For someone who claims to “live as though God exists,” Peterson shows a marked hesitation to accept the God who reveals Himself. As I concluded in that piece, he increasingly resembles a Gnostic prophet of symbolic meaning rather than a faithful witness to revealed truth.

However, the phenomenon of Peterson cannot be dismissed outright. He is neither a prophet nor a fraud. Rather, he serves as a mirror reflecting both the spiritual hunger of our age and its tendency toward intellectual evasion. That so many Christians project their hopes onto him reveals not only the ambiguity of his public posture, but also the depth of the Church’s own crisis of leadership. His apparent, though occasionally reluctant, embrace of a moral and symbolic leadership role only deepens the confusion.

If I am honest, I no longer wait for Peterson’s Pauline moment on the road to Damascus. I imagine something more ironic, such as Christ asking, “Jordan, why do you evade the truth of me in public discourse?”

Even so, judgment must begin with both those who truly follow Christ and those who merely claim to. Peter denied Christ. Most of the apostles fled. And I, too, falter daily. Perhaps Peterson’s struggle is our own, magnified on a public stage. Perhaps he is closer to belief than we think. And perhaps he knows that to cross the threshold of faith would demand everything.

Truth and love converge not in myth, but in the Incarnation. That was the heart of my appeal in “Dear Dr. Peterson”: while symbols may awaken longing, only the Word made flesh can satisfy it.

The road to Emmaus was long. The disciples were unable to recognize Christ at first. But their hearts burned within them as He spoke (Luke 24:13-35).

May Jordan Peterson’s heart burn also.

I find it interesting that there are two outspoken psychologists in Canada: Dr. Peterson and me. One of the major differences between Dr. Peterson and me is that he chooses to “wrestle with God” whereas I prefer to embrace His values. The implications are self-explanatory.