On the Origins of Christmas

Christmas is fundamentally a celebration of the Incarnation—that God became man in the person of Jesus Christ—and as such, it remains a distinctly Christian observance.

There is no shortage of nonsensical ideas circulating throughout both the web on social media and in the mainstream media, much of which does not have any logical basis, or credible historical or scientific evidence.

The Contextual Backdrop

In the case of social media, there has been the resurgence of what is known as “flat earth theory.” The reason I use quotations is because scientific theories, although sometimes discarded or augmented, undergo problem-shifts (a term used by philosopher of mathematics and science Imre Lakatos that shows the malleability of scientific theories for when anomalies arise—not to be confused with paradigm shifts), but they are typically comprised of laws, principles, and facts that help explain what they mean about the world; predictions—that explain what will happen; evidence, which supports theory and cites evidence that may go against it; and testing—a process that looks at whether the predictions made are correct—and flat earth ideology is missing these components that prevent it from being considered a scientific theory, given the body of knowledge we’ve amassed over the centuries. However, a refutation of it is not the subject of this article.

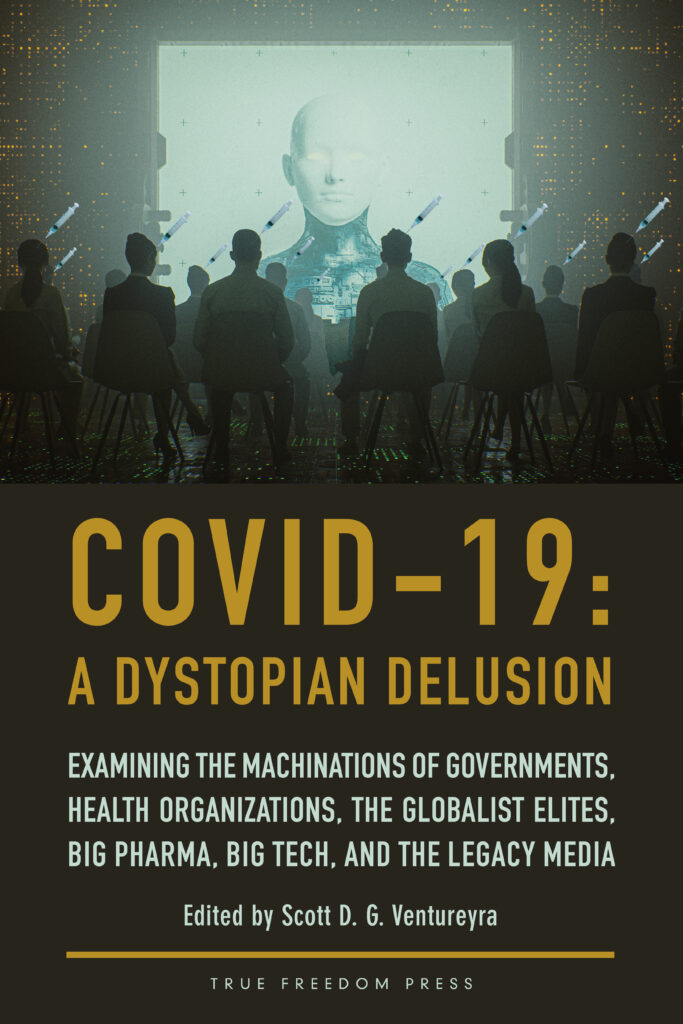

In the case of the mainstream media, they continue to tout the measures taken throughout the COVID fiasco, such as the use of masks, “social” distancing, lockdowns, PCR testing, and its holy grail: that the mRNA COVID vaccines are safe and effective, despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. This is something I discuss in great detail in my book COVID-19: A Dystopian Delusion. And it should be mentioned that, contrary to popular misconception propagated by Covidians (staunch defenders of the COVID narrative), acceptance of the latter does not mean acceptance of the former. This is a facile way of dismissing the strong evidence against the COVID narrative.

Similar to the two aforementioned examples, the claim that the celebration of Christmas, particularly the celebration of Christ’s birth, is borrowed from pagan traditions is a common argument made by critics of Christianity and is based more on wishful thinking than evidence. This argument suggests that the date of December 25th and various customs associated with Christmas have their origins in pre-Christian pagan festivals, such as the Roman festival of Sol Invictus or the Germanic Yule. This assertion is oftentimes lumped together with the ahistorical claim that Jesus never existed and that the Christian narrative is based on pagan mythology, commonly known as the “Christ Myth Theory.” This has been refuted by New Testament scholars, some of whom are not Christians but agnostic about God’s existence, such as Bart Ehrman. He argues against this claim in his book Did Jesus Exist? Nevertheless, these assertions fail to account for the theological and biblical foundations of the Christmas celebration. This article will argue that Christmas is not a pagan festival but rather a Christian observance that was developed based on Christian theological principles and historical events.

The Historical Developments of Christmas

It is important to realize that early Christians, particularly during a period of persecution, had little interest in adopting pagan holidays and festivals. Furthermore, it wasn’t until the 1600s and 1700s that the notion that Constantine created December 25th as the founding date of Christianity was first put forth. It is also worth noting that Christmas falls nine months after the Annunciation, an earlier feast traditionally observed on March 25th. This date has historically been associated with significant events such as the creation of the world, the Incarnation, and the Crucifixion. Additionally, March 25th served as New Year’s Day until the advent of the modern calendar.

The earliest Christians did not celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ, as their primary focus in worship was on His resurrection, which was celebrated during Easter. The first recorded observance of Christ’s birth took place in the 3rd century, designated on January 6th/7th (which is still observed by Eastern Orthodox Christians and some Western Christians), long after Christianity had spread across the Roman Empire. By this time, the importance of Christ’s birth had been recognized and was celebrated by Christians as a pivotal event in salvation history.

The evidence connecting Christmas to paganism is, at best, tenuous, and the date was not borrowed from pagan customs. The choice of December 25th was not random, but likely selected to align with the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere, which occurs around December 21st or 22nd. The solstice marks the point when the days begin to lengthen, symbolizing the arrival of more light. Early Christian thinkers, such as Saint Augustine, believed that this date held symbolic meaning: it was an ideal time to honour the birth of Jesus, the “Light of the World” (John 8:12), who came to dispel the darkness of sin.

While December 25th was also linked to the Roman festival of Sol Invictus, celebrating the sun god, it is important to recognize that Christmas was not directly adapted from this pagan festival. The choice of the date was most likely a practical one, offering Christians an alternative to pagan celebrations and a distinct occasion to commemorate the birth of Christ. However, this does not suggest that Christmas is rooted in pagan traditions.

Biblical Evidence and Theological Significance for Celebrating the Birth of Christ

Although the Bible does not specifically command the celebration of Christ’s birth on a particular date, the New Testament provides strong evidence of the significance of His birth. The Gospels of Matthew and Luke describe the event, highlighting its importance within God’s plan for humanity’s salvation. In Matthew’s account, Jesus’s birth is portrayed as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah (e.g., Matthew 1:22-23, Isaiah 7:14). In Luke’s account, the event is marked by the visit of angels and shepherds, underscoring the extraordinary nature of the birth (Luke 2:8-20).

Even though the Bible does not specify a day for celebrating Christ’s birth, early Christians chose to commemorate it as a way of honouring this foundational event. The doctrine of the Incarnation—the belief that God became man in the person of Jesus Christ—is central to Christian faith and fundamental to salvation history. Celebrating Christ’s birth on December 25th is not a borrowing of pagan traditions, but rather a way of expressing Christian devotion and reflecting on the mystery of God becoming flesh.

Christmas is at its core a Christian feast, focused on the belief that God entered human history through the person of Jesus Christ. The central theological theme is the Incarnation, the moment when the eternal Word of God became man in the womb of the Virgin Mary. As the Apostle John writes in his Gospel, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14). This doctrine of the Incarnation is a foundational belief that sets Christianity apart from other religious traditions.

The view that Christmas is merely a borrowed celebration from pagan festivals fails to recognize the deep theological significance of the holiday. Christmas is not about the winter solstice or sun gods; it is about acknowledging that the Creator of the universe entered human history to offer redemption to a fallen world. Thus, the celebration of Christ’s birth is a reflection of Christian faith, rooted in biblical teachings and Christian doctrine.

Comparing Christmas and Pagan Festivals

It is true that December 25th and some of the customs associated with Christmas, such as feasting, gift-giving, and decorating with greenery, have parallels in various pagan festivals, including the Roman Saturnalia and the Norse Yule. However, these similarities do not prove that Christmas is derived from pagan traditions. All it demonstrates is that cultural practices, such as feasting and exchanging gifts, are common to many human societies and can be found in both pagan and Christian celebrations. The fact that some customs were observed in different cultures does not necessarily mean that one tradition is a direct copy of the other.

For instance, the Roman festival of Saturnalia, held in late December, involved feasting, gift-giving, and social role reversals. Similarly, the Yule celebrations of the Germanic peoples featured evergreen plants, like holly and mistletoe, symbolizing life during the winter months. While these traditions share some surface-level similarities with modern Christmas practices, they do not serve as evidence that Christmas stems from paganism. Instead, it is more likely that early Christians adapted certain cultural elements to fit the celebration of Christ’s birth. For example, the use of evergreen plants in Christmas decorations is rich with Christian symbolism, representing the eternal life offered through Christ.

Critics of the celebration of Christmas further argue that the Scriptures condemn the use of Christmas trees because of their pagan origins, but this is based on a misreading of Jeremiah 10:3-4, which states:

Thus says the Lord: Learn not the customs of the nations, and have no fear of the signs of the heavens, though the nations fear them. For the cult idols of the nations are nothing, wood cut from the forest, wrought by craftsmen with the adze, adorned with silver and gold. With nails and hammers they are fastened, that they may not totter.

This was a warning against the practice of idolatry through that time period, condemning the practice of laying one’s hope in created earthly things as opposed to God’s eternal truths. Jeremiah was most definitely not referring to Christmas trees, as the text appears many centuries prior (the prophet most likely lived in the late 7th and early 6th centuries BC).

On the Christianization of Pagan Festivals

It is also important to recognize that Church teaching does not oppose the idea that God has left true traces of Himself in other world religions, and it is entirely acceptable to “baptize” certain practices from these traditions. This approach mirrors how St. Thomas Aquinas incorporated truths from the writings of the Greek philosopher and pagan Aristotle into Christian thought.

When Christianity spread across the Roman Empire and beyond, it did not seek to erase pre-existing cultural practices but often reinterpreted and transformed them within a Christian context. This process of “Christianization” allowed for the adaptation of cultural elements in ways that aligned with Christian values and teachings.

In the case of Christmas, the use of evergreens and other traditions were reimagined as expressions of Christian theology and devotion. The focus was not on the winter solstice or sun gods, but on the arrival of the “Light of the World” through Jesus Christ. By Christianizing the timing and customs linked to pagan festivals, early Christians honored Christ’s birth while integrating local cultural practices in a way that was both meaningful and reflective of their faith.

Concluding Reflection

In summary, the claim that Christmas is merely a borrowed pagan celebration is unfounded. The same is true of the ahistorical claims about the biblical narrative about Jesus being borrowed by pagan myths, as argued by some critics of Christianity, but that is a subject for another day. Although certain aspects of Christmas may share similarities with pre-Christian customs, Christmas itself is a Christian holiday with deep theological significance rooted in the biblical account of Christ’s birth. The choice of December 25th as the date for Christmas was a practical decision to provide Christians with an alternative to pagan celebrations, but it was not an effort to adopt pagan practices. Christmas is fundamentally a celebration of the Incarnation—that God became man in the person of Jesus Christ—and as such, it remains a distinctly Christian observance. The idea that Christmas is a pagan holiday overlooks its unique theological importance and the transformative influence of Christianity on cultural traditions. We should take to heart the words of St. John Chrysostom’s reflection on Luke 2, known as the “Advent Sermon,” delivered in 386, which offers profound insights into the then newly adapted celebration of Christmas:

What shall I say? And how shall I describe this birth to you? For this wonder fills me with astonishment. The Ancient of Days has become an infant. He who sits upon the sublime and heavenly throne, now lies in a manger. And he who cannot be touched, who is simple, without complexity, and incorporeal, now lies subject to the hands of men. He who has broken the bonds of sinners, is now bound by an infant’s bands. But he has decreed that ignominy shall become honor, infamy be clothed with glory, and total humiliation the measure of his goodness.

For this he assumed my body, that I may become capable of his Word; taking my flesh, he gives me his Spirit; and so he bestowing and I receiving, he prepares for me the treasure of life. He takes my flesh, to sanctify me; he gives me his Spirit that he may save me.

Come, then, let us observe the Feast. Truly wondrous is the whole chronicle of the Nativity. For this day the ancient slavery is ended, the devil confounded, the demons take to flight, the power of death is broken, paradise is unlocked, the curse is taken away, sin is removed from us, error driven out, truth has been brought back, the speech of kindliness diffused, and spreads on every side, a heavenly way of life has been implanted on the earth, angels communicate with men without fear, and men now hold speech with angels.

Why is this? Because God is now on earth, and man in heaven; on every side all things commingle. He became flesh. He did not become God. He was God. Wherefore he became flesh, so that he whom heaven did not contain, a manger would this day receive. He was placed in a manger, so that he, by whom all things are nourished, may receive an infant’s food from his virgin mother. So, the Father of all ages, as an infant at the breast, nestles in the virginal arms, that the Magi may more easily see Him. Since this day the Magi too have come, and made a beginning of withstanding tyranny; and the heavens give glory, as the Lord is revealed by a star.

To Him, then, who out of confusion has wrought a clear path, to Christ, to the Father, and to the Holy Spirit, we offer all praise, now and forever. Amen.

Similarly, the 1965 cartoon film A Charlie Brown Christmas makes clear what the true significance of Christmas is, as opposed to our culture’s obsession with consumerism and propping up of false idols. In the film, the protagonist Charlie Brown asks this fundamental question: “What is Christmas all about?!?” Unlike our decadent culture, Charlie Brown’s friend Linus answers it correctly; he proclaims that it is the birth of Christ. And, indeed, it is.

A Merry Christmas to all!