The Origin, Development, and Contemporary Significances of Early Christian Art

This article was most recently published in The Journal of Biblical Theology 3:4 (October-December 2020): 46–58, which is available in print form.

Abstract: Early Christianity, with respect to the first five centuries, comprises a vast amount of historical data that continues to be unravelled to this very day. The keys to unlocking the “truth,” or rather, the attempt to arrive at the most accurate representation of the past, given our limited knowledge and the available data, lies not only with certain texts but with copious amounts of art embodied through various different forms. These forms can be found in architecture (cathedral, church), iconography (icon, painting, fresco, mosaic), sculptures (Byzantine ivory statues, Catholic plague columns), wood carving, manuscript miniatures, stained glass, oil on canvas, and limited edition reproductions. Due to the nature and limitations associated with historical studies, one must draw an inference to the best explanation. An inference to the best explanation involves ruling out multiple competing explanations for the best one. This is partially accomplished by analyzing the data contextually while using a critical approach (a practice of good hermeneutics). Due to the fact that no one currently living today was around to witness any of the events or formation of the available historical data, one must look at the preponderance of evidence.

Keywords: Byzantine art; Justin Martyr; Christian art; early Christianity; oil canvas; sculptures; wood carving

Early Christianity, with respect to the first five centuries, comprises a vast amount of historical data which continues to be unraveled to this very day. The keys to unlocking the “truth,” or rather, the attempt to arrive at the most accurate representation of the past, given our limited knowledge and the available data, lies not only with certain texts but with copious amounts of art embodied through various different forms. These forms can be found through architecture (cathedral, church), iconography (icon, painting, fresco, mosaic), sculptures (Byzantine ivory statues, Catholic plague columns), wood carving, manuscript miniatures, stained glass, oil on canvas, and limited edition reproductions. Due to the nature and limitations associated with historical studies, one must make an inference to the best explanation. An inference to the best explanation involves ruling out multiple competing explanations for the best one. This is partially accomplished by analyzing the data contextually while using a critical approach (a practice of good hermeneutics). Due to the fact that no one, currently living today, was around to witness any of the events or formation of the available historical data, one must look at the preponderance of evidence. Then one can decide which explanation fits the data more accurately with our current state of knowledge. Moreover, this is precisely why the data must be analyzed critically through exhausting all the possible meanings.

To paraphrase theologian Jonathan Hill, a civilization without any awareness of its history is akin to a person without a memory.[1] This insight underlines the importance of understanding our past. Understanding our past can provide us with valuable knowledge to unravel the mysteries of antiquity. It can also potentially aid in future developments and provide information to avoid the mistakes committed by our ancestors. Likewise, early Christian art gives us an illuminating glimpse at the early Christian world, which has provided and continues to provide historians and theologians with valuable knowledge about Christianity’s deep history. This paper will examine the origins and development of Christian art (which are deeply indebted to its influences that have been derived from different styles and schools of thought) and the significance of early Christian art in lieu of pedagogical functions.

In our present day, it may be difficult to imagine a period when Christian art did not exist. This could be because we have been inundated with Christian art and symbols in the Western world. Undoubtedly, it is deeply embedded in Western consciousness. However, according to C.R. Morey, there was a period where “craftsman essayed to paint, or carve, or build for the first time something that was to be Christian, with nothing to show them how it should look.”[2]

The earliest traces of Christian art are commonly dated towards the end of the second century.[3] Based on the collection of ancient art, we know how Romans, Egyptians, and Greeks appeared to be, but no images of David, Solomon, or any important Israelite figures have been discovered.[4] Joseph Kelly notes that this custom “survived into Jesus’ day and explains why the Christians made no image of him from life.”[5] A large number of scholars believe that Christian art did not surface until the third century because Christians, as Robert Jensen states, “observed the Jewish prohibition against the production or use of figurative images for religious purposes—a prohibition established by the second commandment” (Exodus 20:4-5).[6] In some instances scholars believe that this delay can be correlated with Christians wanting to be disassociated from, as Jensen observes, “their idol-worshipping neighbors, whose cult statues or religious images were understood to be the work of demons.”[7] According to Christian apologist Justin Martyr, in his work I Apology (9:1–9), he cites that the pagans honoured cult images with sacrifices while portraying the Christians as finding such practices lifeless, empty, and insulting to the “true God.”[8]

Moreover, Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian both maintained that attributing wood or stone qualities to infinite divinity was absurd and at times “obscene.”[ix]

Textual evidence seems to suggest that certain theologians did indeed go against the production of cultic art objects for the practice of idolatry while perhaps understanding the difference between that and the functional uses of art, whether it was decorative, symbolic, or didactic.[x] Christians probably understood that smaller objects did not have much significance. So when larger objects did come on to the scene, it was not a great shock since they were not seen as objects of worship, and as Jensen observed, they “therefore presented no danger of idolatry.”[xi] Some scholars believe that many of the Christian converts who came from a polytheistic background abandoned their old practices since they recognized that they were incompatible with their new faith. However, at the same time, it seemed as though they were inclined to adapt certain habits to their new faith. Jensen notes that a number of scholars believe that “Christian” motifs appear to have been modelled on Graeco-Roman prototypes, albeit reinterpreted to have particular Christian significance.[xii] According to Jensen, perhaps the most famous example of “this translation from polytheist to Christian artistic type is the Good Shepherd, displayed as a youth dressed in a short tunic and boots, carrying a ram or lamb over his shoulders.”[xiii] This very renowned figure was adopted from the figure of Hermes as a guide to the underworld, usually associated with funerary contexts.[xiv] The Good Shepherd was used metaphorically for both God and Jesus in John 10. Luke 15:6 also contains a passage saying, “When he [the shepherd] has found it [the lost sheep], he lays it on his shoulders, rejoicing.” Christians could readily associate the iconography with their already-inherited beliefs based on the scriptures or oral tradition.[xv] Other examples of adoption would include a dove, which would symbolize the Holy Spirit, as Kelly states, “as would an anchor, a symbol of hope.”[xvi] Clement of Alexandria, despite his apparent condemnation of using iconography as a form of idolatry, according to Kelly, proposed that “when Christians used their signet rings, they should use Christian symbols, such as the dove or a ship (for the Church) or a fish, an anagram for Christ, that is, a word made from the first letters of a phrase. The Greek word for fish included the initial letters for a phrase, “Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Savior.”[xvii]

As seen above, many writers condemned the usage, production, or worship of “graven images,” which were strictly prohibited by divine law or because of the potential lure for Christians in performing such an act. The same writers, as Jensen states, “provide testimony that Christians both used and perhaps produced small, everyday objects that carried specific Christian symbols.”[xviii] Some of these objects, which included gems, glassware, and lamps that can be found in museum collections today, were made by Christian craftsmen for Christian consumers.[xix] It is evident that when the Jews and Christians parted ways, and because of the subsequent conversions of many Gentiles to Christianity, the use of visual images increased significantly.[xx] Christian leaders were stifled by the question of whether the followers of Christianity should be allowed “representational art,” as more and more of them increasingly wanted to design images of Jesus, his family, and his disciples.[xxi] These Christian leaders faced a tremendously difficult question that was consequently the root of much controversy throughout Church history, from the times of Leo I to Constantine V to the Reformation.[xxii]

The philosophical climate of the third century itself was highly dualistic and was opposed to materialism. Plotinus, among others, were instructing against materialism. Matter was seen as a hindrance to the spirit, not a mirror to it and as Syndicus observed, “was no longer considered right to express things of spiritual significance in an ideal form.”[xxiii] Furthermore, Syndicus notes that Christianity is “just as far removed from the rejection of the world as it is from undue devotion to it.”[xxiv] This is the key to understanding the acceptance of Christian art. Christians recognize that they belong to a higher cosmic reality outside of this material world, which is their destiny to attain, but at the same time, they are inescapably connected to the material aspect of this world, which serves as a trial for the worthiness of the spiritual world. These outlooks and realizations are quite essential because, similarly, according to Syndicus, “Christian art has to take the path from realism to symbolism, which removes the supernatural from what is only too near and comprehensible.”[xxv] Christian art created a new form of expression, a vocabulary, if you will, through the available forms of classical art. This begets a complicated question: where did Christian art originate?

One of the most important aspects of the development of a particular art is the influence of different styles. D. Talbot Rice, in his book, The Beginnings of Christian Art, eloquently expounds the significance of each legacy of Christian art from different regions and their service to Christian faith:

No art is born suddenly out of nothing; continuity has always been an essential of every phase, and it was especially important in early Christian art. All the regions of the nearer East where Christianity was first preached and practiced had something to give, and there has been a good deal of argument as to which of them – Rome, the Hellenistic world, the east Mediterranean lands that were under Iranian influence – exercised the principal role. This argument, which has often in the past been colored by a definite partisanship, is not taken up again here. Instead an attempt is made to show what was actually the legacy of each region, and how it was taken over and developed in the service of Christian faith.[xxvi]

Rice presents three different styles of art: the picturesque style, the expressionist style, and the neo-attic style, each of which traces its origins to particular regions.

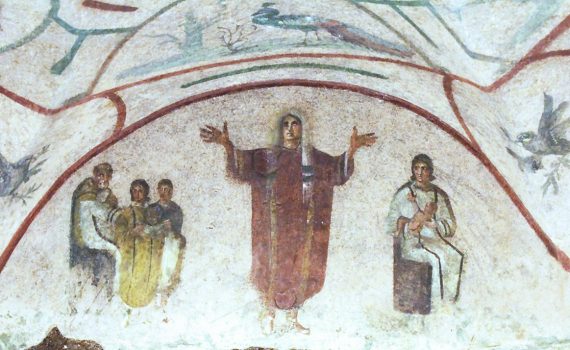

First, the picturesque style, shaped by its dedication to landscape and elegant architectural decoration, was developed in Pompeii. Rice goes on to suggest that there is “no doubt that it existed in Alexandria also,”[xxvii] but without giving evidence for it, he says that “no examples have come down to us.” It may be better to conclude that there may be reasons to believe it existed in Alexandria, but that as of yet there is no direct evidence to support this assumption. The late-century work in the catacomb of Domitilla provides strong evidence for this “picturesque” style, primarily in the scene of the Good Shepherd.[xxviii] Jesus is depicted in a landscape surrounded by trees and animals. The theme of the scene is obviously Christian, but it strongly embodies pagan motifs.[xxix]

Second, the expressionist style is described by Rice as “more emotional, more violent,” which is the terminology that was current during the 1950s for art criticism.[xxx] Scholars believe that this type of art lacked “delicacy.” Rice goes on to suggest that it was similar to the sculpture of ancient Mesopotamia: “it was essentially in the same style, and a search for emotion and expression characterized the art of Asia Minor in Hellenistic times.”[xxxi] Some scholars believe that the “expressionist” was conceived in Asia Minor, as suggested by Morey and others in Syria.[xxxii] Rice attests that “it was mainly thanks to the influence of Syria that the style spread to other places, and nowhere was it more intensively developed than in Egypt.”[xxxiii]

The “neo-attic” style played a pivotal role in the formation of Byzantine art and for all early Christian art, according to Morey.[xxxiv] It was developed as a rather conservative Hellenic style two centuries prior to Christ’s birth. It was therefore starkly contrasted from the two other styles. Antioch was a major site for “neo-attic” style according to expert, Morey.[xxxv] This particular style went beyond the eastern Mediterranean and seemed to have flourished in Rome. An example of “neo-attic” style would be that of a piece of silver; Rice indicates that it would be “bearing an elegant if rather severe figure seated frontally with animals and birds at the sides, which has been identified as a personification of India.”[xxxvi]

Important insights on the development of Christian art include depictions of Old Testament art that seem to have predated those of the New Testament; Old Testament artistic figures in the catacombs predate those of the New Testament. This is not surprising to scholars since the Old Testament was already translated into “Alexandrian Greek” much before the Christian era.[xxxvii] The motifs that were most embodied in the catacombs early on were of “sin and death,” which were first found in the stories of the Old Testament through the flood and Noah’s Ark, representing salvation from the “deluge” of sin.[xxxviii]Only after 200 C.E. can those frescoes be readily correlated with the miracles of Jesus. Another important piece of evidence suggesting why Old Testament artistic interpretations preceded those of the New Testament is, as some scholars believe, because people were familiar with illustrated books of the Old Testament, which, as Morey affirms, were “first produced in Alexandria, where the first Greek version of the Old Testament was made.”[xxxix]

Three prominent styles emanating from different regions had a positive impact on early Christian art, as was the case with the influence of Jewish exemplars and pictorial art. Of the known catacombs in Rome, one by the name of Via Latina was discovered in 1955 and has been described as very rich in “pictorial decoration,” making it very hard to adequately explain.[xl] The actual work, besides depicting Jesus, Peter, and Paul, undoubtedly a Christian motif, carries many pagan motifs, unlike the majority of pictures derived from the second until the fourth century, which portray biblical scenes of the Old Testament.[xli]

The influence of Jewish pictorial art was quite widespread, as evidenced by the discovery of the Via Latina Catacomb. Jewish art had already developed a picture programme by the third century, which was around the time of the beginnings of Christian art. This is exemplified by Schreckenberg and Schubert’s statement that “such picture programmes are also attested in Christian sources from the fourth century on; it is difficult to draw any other conclusion than that Christian artists employed optical Jewish exemplars.”[xlii] Furthermore, according to Schreckenberg and Schubert, scholars who strongly support the influence of Rabbinic tradition believe that even in the Via Latina Catacomb it is possible to “conclude the probability of Jewish influence in many examples,” but they acknowledge that “an additional Christian understanding can be presumed.”[xliii]

An example that Schreckenberg and Schubert attest to having convincing Jewish influence is that of the Moses Sequence in Cubicula C and O. The frescos in the Cubicula C and O demonstrate a Christian reinterpretation that can be traced to an “originally Jewish sense.”[xliv] The right wall shows the Israelites crossing the Red Sea, and on the left, a scene is depicted with strong similarities to the resurrection of Lazarus. Schreckenberg and Schubert indicate that “the more recent version from the second half of the fourth century in Cubiculum O has a Lazarus figure added.”[xlv] It is currently believed that the picture sequence in Cubiculum C is older than the O, which carries the “variant,” so Schreckenberg and Schubert believe that it should be “attempted first of all to account for the details of these scenes in Rabbinic Scripture interpretation on the basis of C.”[xlvi] Regardless, it is clear that Christians have read their own interpretations into several of these art forms. The addition of Lazarus is strong evidence of this. Scholars believe that Cubiculum C is fifty years older than Cubiculum O and have believed that even without the addition of Lazarus, the conclusion is the same.[xlvii] Schreckenberg and Schubert note that the Israelites’ crossing of the Red Sea “with dry feet could be understood as a symbol of Christian baptism, to which, on the other hand, God’s presence and his Law as antitypes for Christ and the New Testament corresponded.”[xlviii] The authors conclude that the Moses Sequence and many other art works in the Via Latina catacomb can be traced to the influence of its Rabbinic tradition. Moreover, the fact that the art work “appear[s] to stem from Jewish figurative exemplars, must suffice to demonstrate that Jewish figurative art was one of the sources from which early Christian painting benefited.”[xlix]

A significant aspect of early Christian art is that of the functional uses of iconography, i.e., its pedagogical purposes. The combination of the Greek words “eikon” and “graphe” is essential. Eikon means image and graphe means writing, so technically, iconography signifies “writing with images.”[l] The use of iconography in Christianity was essential because many of its adherents were not literate. Therefore, pictures became essential for conveying messages to the illiterate. The following quote by Kelly captures this notion perfectly:

Significantly, this earliest reference to Christian art involves iconography… [commonly regarded] as a source for our knowledge of the early Christians. Christians viewed art as they viewed the Bible, the one a verbal, the other a visual representation of reality beyond words or images. While some art offered portrayals of biblical or Christian scenes, much of it intended to point to other realities. Conveniently, this was also the way in which Christians warded off charges of idolatry, that is, no one worshipped the image, which would be idolatrous, but rather the reality to which it pointed.[li]

Even to this day, pictures are used effectively for political campaigns or marketing ploys.

Some other uses seem apparent. According to Kelly, in the ancient pagan world, when artists wanted to aid people in visualizing a divinity, “they portrayed light emanating from the head in the form of a circle, [which was] called a nimbus.”[lii] Jesus was often portrayed with a special nimbus. Christians also emulated the motif of “wings” to symbolize certain figures as belonging to another world.[liii]

The origins and development of early Christian art are indebted to a number of factors. These factors are comprised of certain styles associated with certain regions and practices, converts to Christianity adopting pagan practices, and more than purely aesthetic functions such as pedagogical uses. Early Christian art did not spring forth without its ancestral roots; rather, it is seen as an undisrupted continuous seam extending to ancient religions and practices.

[1] Jonathan Hill, The History of Christian Thought (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2003), back cover.

[2] C. R. Morey, Christian Art (New York: Norton & Company, 1958), 5.

[3] Robin M. Jensen, “Art” in The Early Christian World, ed. Philip F. Esler (New York: Routledge, 2000), 747.

[4] Joseph F. Kelly, The World of the Early Christians (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1997), 133.

[5] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 133.

[6] Jensen, “Art,” 747.

[7] Jensen, “Art,” 747.

[8] Jensen, “Art,” 747.

[ix] Jensen, “Art,” 747.

[x] Jensen, “Art,” 748.

[xi] Jensen, “Art,” 748.

[xii] Jensen, “Art,” 748.

[xiii] Jensen, “Art,” 748.

[xiv] Jensen, “Art,” 748.

[xv] Jensen, “Art,” 748.

[xvi] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 134.

[xvii] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 135.

[xviii] Jensen, “Art,” 747.

[xix]Jensen, “Art,” 747.

[xx] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 133.

[xxi] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 134.

[xxii] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 134.

[xxiii] Eduard Syndicus, Early Christian Art (London: Hawthorn Books, 1962), 32.

[xxiv] Syndicus, Early Christian Art, 33.

[xxv] Syndicus, Early Christian Art, 33.

[xxvi] D. Talbot Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art (New York: Abingdon Press, 1957), 17.

[xxvii] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 28.

[xxviii] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 28.

[xxix] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 26.

[xxx] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 28.

[xxxi] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 30.

[xxxii] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 43.

[xxxiii] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 43.

[xxxiv] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 45.

[xxxv] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 45.

[xxxvi] Rice, The Beginnings of Christian Art, 52.

[xxxvii] Morey, Christian Art, 8.

[xxxviii] Morey, Christian Art, 6.

[xxxix] Morey, Christian Art, 8.

[xl] Heinz Schreckenberg and Kurt Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991), 189.

[xli] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 189.

[xlii] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 190.

[xliii] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 191.

[xliv] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 191.

[xlv] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 197.

[xlvi] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 197.

[xlvii] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 197.

[xlviii] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 198.

[xlix] Schreckenberg and Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography, 209.

[l] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 34.

[li] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 135.

[lii] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 34.

[liii] Kelly, The World of the Early Christians, 34.

References

Esler, Philip F, editor. The Early Christian World. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Hill, Jonathan. The History of Christian Thought. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2003.

Kelly, Joseph F. The World of Early Christians. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1997.

Lipton, Peter. Inference to the Best Explanation. New York: Routledge, 1991.

More, C. R. Christian Art. New York: Norton & Company, 1958.

Rice, Talbot D. The Beginnings of Christian Art. New York: Abingdon Press, 1957.

Schreckenberg, Heinz, and Kurt Schubert. Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992.

Syndicus, Eduard S.J. Early Christian Art. London: Hawthorn Books, 1962.