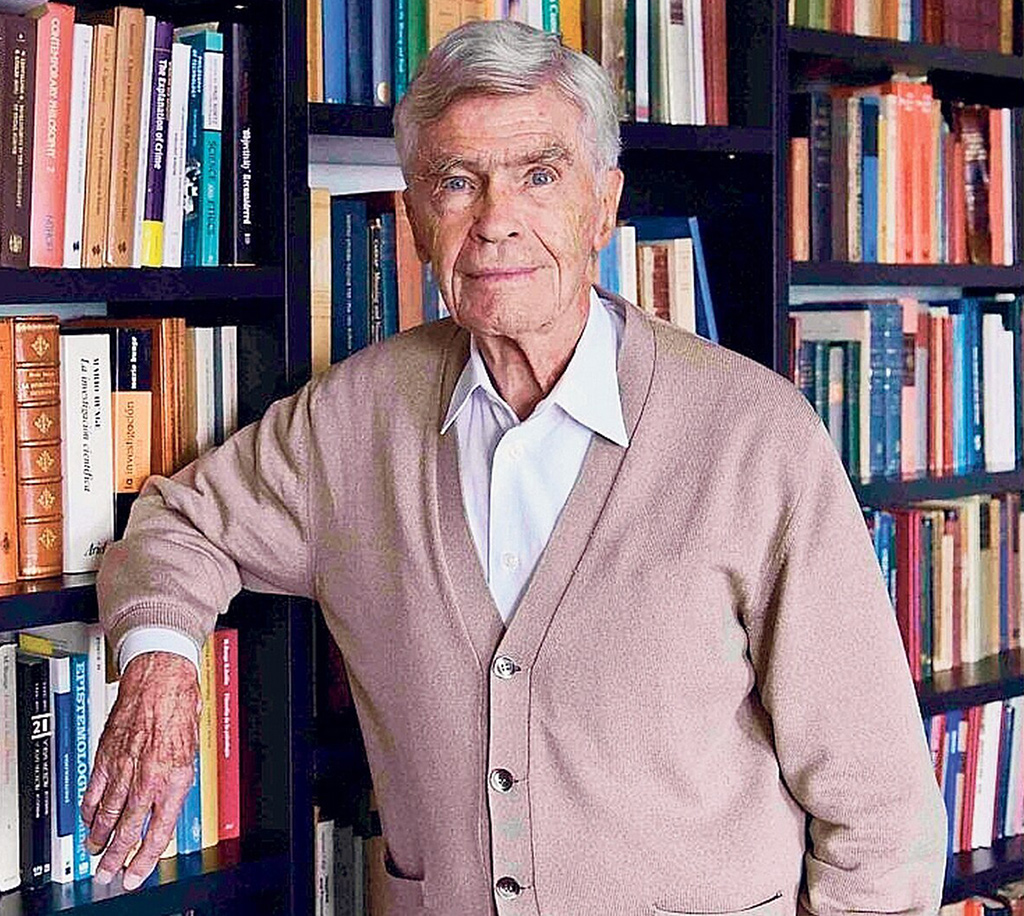

A Reflection on Mario Augusto Bunge’s Life and Work

On February 24, at 100 years of age, physicist and philosopher Mario Augusto Bunge passed onto the next life. Bunge completed a PhD in physico-mathematical sciences from the Universidad Nacional de La Plata in 1952 (the same university that my father completed his medical degree at in 1970).

On February 24, at 100 years of age, physicist and philosopher Mario Augusto Bunge passed onto the next life. Bunge completed a PhD in physico-mathematical sciences from the Universidad Nacional de La Plata in 1952 (the same university that my father completed his medical degree at in 1970). He had sixteen honorary doctorates and four honorary professorships. He was also a prolific author, having written over four hundred papers and eighty books. He’s one of the most cited Spanish-speaking scientists and philosophers in history, as well as one of the most famous physicists of the past two hundred years. His 1959 work, Causality: The Place of the Causal Principle in Modern Science, was ground-breaking and translated into seven languages. In it, he argued for an expanded principle of determinism to be applied to modern science. He spoke and wrote vociferously against what he considered pseudoscience. He was critical of Marxism, postmodernism, psychoanalysis, alternative medicine, logical positivism, and existentialism.

Remarkably, Bunge was a self-trained philosopher. He was a rare thinker. As an atheist and scientific materialist, he took both philosophy and the natural and social sciences seriously. Scientific materialists throughout the past hundred years or so, because of their ignorance of philosophy, have had an irrational aversion to it. But, of course, for any bona fide intellectual, this would be contradictory to reason since philosophy is fundamental and indispensable to the scientific method. (I have argued this in chapter 2 of my book, On the Origin of Consciousness.) He worked diligently to remove cultural ignorance about philosophy. An example of this was in both his lectures and writings geared toward medical doctors, who understood the importance of philosophy. Interestingly, he saw a synergy between metaphysics and science. Volumes 3 and 4 of his Treatise on Basic Philosophy emphasized the importance of metaphysics.

Postmodernism

We do not have the space to explore all of the ideologies, pseudo-sciences, or modes of thought Bunge critiqued, so I’ll focus on just one: postmodernism. Postmodernism can be viewed as a disastrous thought experiment, or what physicists Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont accurately dubbed “fashionable nonsense.” It is important to note that postmodern “philosophers” such as Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Francois Lyotard, and their faithful disciples, through their works, have vehemently denied objective truth, metaphysics, and consequently any metanarrative. Metanarratives are fundamental to any coherent worldview. They have sought to uproot the philosophy of history, the history of philosophy, and history in general as relating to a power struggle as opposed to a pursuit of truth. Incoherently, by denying the ultimate truth, they affirm it; there’s no escaping this logical misstep. Philosophical pursuits, if we can call them that, under a postmodern epistemological guise, are to be localized and subjective. In other words, they are relativistic. Nevertheless, one of the sole fruits of postmodernism lies in its ability to force one to make more precise analyses and deductions based on questions of specificity. The view I have just expounded here aligns well with Bunge’s, as is found in a passage of his book, Between Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Philosopher-Scientist:

A philosophy without ontology is invertebrate; it is acephalous without epistemology, confused without semantics, and limbless without axiology, praxeology, and ethics. Because it is systemic, my philosophy can help cultivate all the fields of knowledge and action, as well as propose constructive and plausible alternatives in all scientific controversies (406).

Furthermore, in an article published in 1995 in the journal Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, titled “In Praise of Intolerance to Charlatanism in Academia,” Bunge scathingly writes the following about postmodernism:

Over the past three decades or so very many universities have been infiltrated, though not yet seized, by the enemies of learning, rigor, and empirical evidence: those who proclaim that there is no objective truth, whence “anything goes,” those who pass off political opinion as science and engage in bogus scholarship. These are not unorthodox original thinkers; they ignore or even scorn rigorous thinking and experimenting altogether. Nor are they misunderstood Galileos punished by the powers that be for proposing daring new truths or methods. On the contrary, nowadays many intellectual slobs and frauds have been given tenured jobs, are allowed to teach garbage in the name of academic freedom, and see their obnoxious writings published by scholarly journals and university presses. Moreover, many of them have acquired enough power to censor genuine scholarship. They have mounted a Trojan horse inside the academic citadel with the intention of destroying higher culture from within (96).

This point could not have been more brilliantly made. The situation has only drastically worsened since 1995. Unfortunately, this sort of thought runs rampantly throughout our unthinking culture, which gravitates more and more towards relativism; we see this with the cancel culture and the attempt to annihilate free speech and reason. What makes things significantly more sinister is that the general population is unaware of their tax dollars being used to fund this rubbish. Wishful morticians of the absolute (as I sometimes refer to postmodernists) toy with the very fabric of Western civilization and yet take advantage of its fruits, a hypocrisy of the highest order. It’s like the social activist who decries capitalism and yet does so by using state-of-the-art technology. It’s an irreverent form of narcissism that’s pathological to its core. It lies somewhere between ignorance, malevolence, and insanity. Such lunacy can only serve the pedagogical purpose of teaching how not to think and act. As I wrote in my article for Crisis Magazine in 2017, Canada’s Free Speech Wars:

Sokal in 1996 brilliantly exposed postmodernism’s abuse of science and reason with a submission of a hoax article, with the absurd title: “Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity” to Social Text, a prominent postmodern cultural studies journal.

In more recent years, such abuse has been exposed even more forcefully by magazine editor Helen Pluckrose, mathematician James Lindsay, and philosopher Peter Boghossian through authoring a series of purposely nonsensical articles that were published in prominent postmodern and grievance studies journals. For example, feminist journal Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work published an article that was a re-writing of Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” through a feminist ideological perspective.

Scientific Materialism

Although I disagree with scientific materialism (a position that Bunge defends) and have written against this philosophy in many of my writings, I must admit that he argues for this position more persuasively than any of the neo-atheists or contemporary scientists could ever dream of. Despite profound disagreements in this area, I had asked Bunge to endorse my book on consciousness in 2018. I was surprised at not only the fact that he replied but also with such promptness, which was a testament to his lucidity and technological savviness. In his reply, he stated the following:

Hello Dr Ventureyra,

Thank you for thinking that I might endorse your book, but that won’t be possible, because I have argued repeatedly for a scientific materialist view of the mental.

Sincerely,

Mb

A Kind of Kinship

Nevertheless, I have felt some affinity for his work’s rigour, profundity, and innovation. I had also felt some kinship with the man without ever having met him. Like myself, Bunge was both Argentinian and Canadian. Nonetheless, in one of his last interviews, he said he didn’t think much about Argentina since, according to him, within the last hundred years it had ceased to be an important country because of multiple dictatorships’ economic, political, and social crises. I can’t say I disagree with this assessment given the downward spiral the country has faced with destructive and corrupt governments.

Bunge also seemed to be a quirky man with a good sense of humor. For example, in an interview for elPeriódico.com in 2009, the reporter asked Bunge about his secret to looking so youthful at ninety years old, and he hilariously responded, “That’s because I avoid alcohol, tobacco, and postmodernism.” It seems inescapable that good thinkers will unceasingly poke at and beat postmodernism. In light of this sense of humour, I can’t help but think of a joke iterated in a fictitious scene in the Netflix movie Two Popes. The scene involves a conversation between the actor Jonathan Pryce, who portrays Argentine Cardinal Bergoglio (now Pope Francis), and Pope Benedict XVI (played by Anthony Hopkins): “Do you know how an Argentinian commits suicide?” “He climbs to the top of his ego and jumps off!” Self-inflated egos seem to follow academics, perhaps more so with Argentinian ones.

My friend, William Sweet, who is a prominent Canadian philosopher and a fellow member of the Canadian Jacques Maritain Association, recently recounted an amusing story about Bunge. During the period prior to the 1995 Quebec referendum, at the yearly Canadian Philosophical Association, Bunge, in the presence of some philosophers who were Quebec separatists, made a toast: “To the unity of Canada!” A colleague quickly made another toast: “To the unity of Professor Bunge!” One can only imagine the separatists’ faces after Bunge’s toast. Bunge was a man who spoke his mind without much reservation.

Lover of Wisdom

Whether we agree or disagree with Bunge on any number of philosophical or scientific issues, one thing is clear: he thought deeply and passionately about some of the most difficult problems in metaphysics, epistemology, and the philosophy of science. He sought to integrate philosophy and science with what he identified as a “scientific philosophy.” This would be something distinct but not too dissimilar to Teilhard de Chardin’s “scientific theology.” I, myself, have sought to integrate science, philosophy, and theology. To understand the world and ourselves, we need a holistic approach that can be integrated. We shared the view that knowledge should be unified.

He also emphasized the importance of passion for philosophers regarding their pursuit of philosophical problems and questions; this is what he attributes to maintaining his mind so sharp nearing the end of his life. He was a true philosopher, that is, a true lover of wisdom, a person who Plato, in his work Symposium, would describe as being between the wise and the ignorant. Even though, most people do not make good philosophers, we all philosophize as finite beings; and we cannot be found anywhere else but between wisdom and ignorance. This is a sign of our limitations and a testament to why we should always remain humble and hungry for knowledge. Bunge pursued truth through his passion for writing and teaching. He has left us with many important intellectual contributions. In these trying times of extreme ignorance and irrationality, rational theists can find allies in rational secular thinkers like Bunge since they affirm the existence of truth, goodness, and justice. The theist can, in a strange way, find closer proximity to the rational atheist than theists who adhere to postmodernism, for instance. Nevertheless, perhaps now his journey has been extended to discover eternal truths—that there is a reality that transcends the physical.

I offer mutually beneficial cooperation http://fertus.shop/info/