Thomas Aquinas’s Understanding of Faith and Reason: Jacques Maritain and Norman Geisler in Dialogue

This article was most recently published in the Journal of Biblical Theology 2:3 (October–December 2023): 5–22, which is available in print form.

Abstract

This article examines the thoughts and works of Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain and evangelical philosopher Norman Geisler in light of their understanding of Thomas Aquinas’s view of faith and reason.

Keywords: faith; faith and reason; Jacques Maritain; Norman Geisler; reason; the relationship between faith and reason; Thomas Aquinas; Thomism

Introduction

This article will examine the works of two influential interpreters of Thomas Aquinas: the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain and the late evangelical philosopher Norman Geisler. The particular focus of this paper will be on the two interlocutors’ own understanding of faith and reason alongside their interpretation of Aquinas’s view on the matter. I will also briefly consider how Aquinas’s work has impacted their own work and faith and whether a study of Aquinas needs to lead to Catholicism, for instance. It is important to recognize that the relationship between philosophy and theology as it pertains to faith and reason is an inextricable interaction. Philosophy functions as a method of reasoning to tackle deep questions about reality, such as the existence of God, as exemplified by natural theology. However, theology, although it makes great use of philosophical thought, is not reducible to it. Theology operates from a faith in things revealed but reasons through them to create greater acts of understanding of the profundities of the Christian faith, which are rooted in truth, love, and goodness. It provides a gateway into recognizing the ineffable while acknowledging the deep limitations of such tools in discerning the eternal mysteries of God.

First, I’ll begin with a few words on Norman Geisler since I suspect that neither he nor his works will be very familiar to those in attendance today.[1] Second, I’ll look at his own views and interpretation of Aquinas’s understanding of faith and reason. It is indeed an interesting take on Aquinas given that, broadly speaking, protestants, and more particularly, evangelicals, have had an aversion to scholasticism and Thomistic thought. Martin Luther left behind a peculiar legacy that created a rift between Protestantism and Scholasticism and, more generally, between faith and reason. Geisler, in my estimation, tears down such misplaced aversions. Third, I’ll examine Maritain’s take on faith and reason and his interpretation of Aquinas. From there, I will seek to draw some threads between these two views and some of the impact that Aquinas’s thought has had on their work.

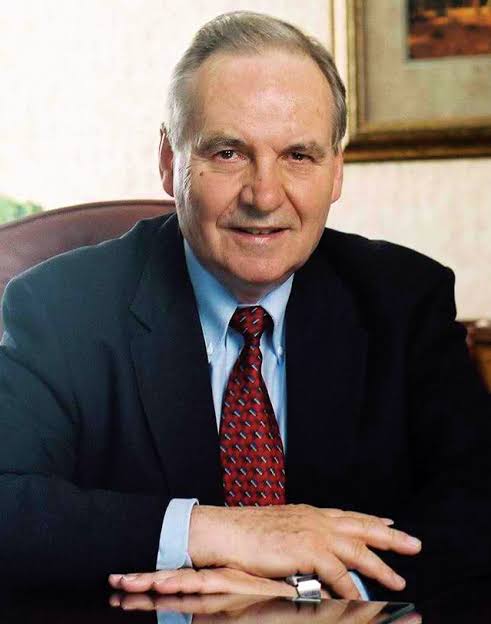

On Normal Geisler

Geisler passed away at the age of 86 on Canada Day this year. He was a prolific writer who authored over 125 books and hundreds of articles. He was known for merging evangelicalism with philosophy. He graduated with a PhD in philosophy from Loyola University, a Jesuit university. He developed a warm affinity for Aquinas’s work. Although he remained a Protestant himself, throughout his studies he grew to appreciate the richness of the intellectual Catholic tradition. Even though he maintained disagreements, he sought to build bridges between Catholics and Protestants in both everyday life and academic circles. He was often described as being a cross between Billy Graham and Thomas Aquinas[2] since he had the heart of an evangelist and also the rigour and argumentation of a good philosopher. Reason was his vehicle to proclaim the Gospel. Amusingly, before he pursued his academic career in theology and philosophy, he was humbled by a drunkard when attempting to preach the Gospel upon his conversion after finishing high school. Keep in mind that at this stage in his life, Geisler had not even read a single book. Thus, when Geisler gave the drunkard a pamphlet welcoming him into a rescue mission in Detroit, the drunkard grabbed his Bible and turned to Matthew 8:4, reading “Jesus said go and tell no man,” then told Geisler to leave since Jesus didn’t want him doing this. Geisler was speechless; he had been stumped by Mormons, Jehovah Witnesses, and now a drunk. So, Geisler, through these experiences, realized that he should stop witnessing or equip himself in order to answer difficult questions regarding the Christian faith. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, when Geisler started his research into apologetics, there weren’t any contemporary works of Christian apologists in the US, aside from a book by Gordon Clark or Cornelius van Til.[3] Remarkably, since then, he has managed to pave the way for evangelical philosophy and Christian apologetics in the twentieth century by influencing philosophers and apologists such as William Lane Craig, JP Moreland, Francis Beckwith, Ravi Zacharias, and countless others. Some of these scholars published an edited volume in 2007 in honour of Geisler, titled To Everyone An Answer, which was published by InterVarsity Press.

The late Thomistic philosopher, Director of the Jacques Maritain Center, and Michael P. Grace Professor of Medieval Studies at the University of Notre Dame, Ralph McInerny, had this to say in the forward to Norman Geisler’s book on Aquinas, titled Thomas Aquinas: An Evangelical Appraisal: Should old Aquinas be forgot? Many say yes, but the author says no!:

Regarding Geisler’s landmark volume, in which he straightforwardly confronts notable evangelical rejections of, or at least, cautions about, Aquinas, and seeing the life and writings of the man who has been my philosophical mentor for some forty years freshly presented in a new and surprising light, made me think once again what poor stewards of Aquinas’s thought we Thomists have been. If, as Geisler argues, Aquinas has come under evangelical fire for holding things he did not hold, I sometimes think that Thomists have commended him for positions that are not his.… I am flattered and pleased to have been asked to say a few words by way of introduction to this extraordinary book. Dr. Geisler is a man I have known and admired for many years. It is indeed the rare man who can find in an apparent enemy an ally. But Geisler’s study of Thomas Aquinas is far more than an instance of the old adage fas est et ab hoste doceri (it is right to learn even from the foe). He enables evangelicals and Catholics to see the immense range of truths that unite us, not as some least common denominator, but truths that are at the heart of our Christian faith.[4]

Geisler on Aquinas’s Understanding of Faith and Reason

Following Aquinas, Geisler understands that faith uses reason and that reason is incapable of functioning without faith. Thus, Geisler sees Aquinas’s view of faith and reason as deeply interrelated but distinguishable: Although Aquinas did not actually separate faith and reason, he did distinguish them formally. He affirmed that we cannot both know and believe the same thing at the same time.[5] He then quotes Aquinas to support this perspective: “whatever things we know with scientific [i.e., philosophical] knowledge properly so called we know by reducing them to first principles which are naturally present to the understanding. All scientific knowledge terminates in the sight of a thing which is present [whereas faith is always in something absent]. Hence, it is impossible to have faith and scientific [philosophical] knowledge about the same thing.”[6]

He views Aquinas’s understanding of reason as being intrinsic to a deep faith but incapable of producing faith.[7] In demonstrating this, he quotes Aquinas on Ephesians 2:8–9 as found in the Commentary on Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians stating that “free will is inadequate for the act of faith since the contents of faith are above reason… That a man should believe, therefore, cannot occur from himself unless God gives it.”[8] Therefore, faith is seen as a gift from God, without it, faith is not possible. As Aquinas himself iterates: “faith involves will (freedom) and reason doesn’t coerce the will.”[9] So that people are free to choose not to believe, even though the reasons for believing may be convincing.

In discussing Christianity, when the authority of Scripture is rejected by those outside of the faith, an appeal to reason can be made. An example would be discussing Biblical truths with a Muslim or skeptic. The groundwork has to be laid prior to discussing the claims of Christian truths within the Scriptures. Certain truths can be attained by reason, as Aquinas states: “Such are that God exists, that He is one, and the like. In fact, such truths about God have been proved demonstratively by the philosophers, guided by the light of the natural reason.” Geisler understood that Aquinas thought that reason had three important uses within the Christian faith: first, to prove natural theology, for God’s existence and nature; second, to demonstrate supernatural theology, such as the Trinity and the incarnation; and third, to refute false theologies or heresies.[10]

Geisler understood divine authority as the basis of faith in Aquinas’s thought since reason itself cannot provide the basis for believing in God. One can demonstrate God’s existence but cannot convince others to believe in God when there’s resistance.[11] As Aquinas states “faith does not involve a search by natural reason to prove what is believed. But it does involve a form of enquiry unto things by which a person is led to belief, e.g., whether they are spoken by God and confirmed by miracles.”[12] For instance, demons are convinced of God’s existence but as Aquinas shows “it is not their wills which bring demons to assent to what they are said to believe. Rather, they are forced by evidence of signs which convince them that what the faithful believe it true…. [and yet] these signs do not cause the appearance of what is believed so that the demons could on this account be said to see those things which are believed. Therefore, belief is predicated equivocally of men who believe and of demons.”[13]

Since faith involves the will to believe, it possesses a meritorious nature. In reference to Hebrews 1:11, Geisler finds a strong definition of faith in terms of not only what it does but what it is—three essentials—through quoting Aquinas:

First, from the fact that it mentions all the principles on which the nature of faith depends… [namely, the will, the object (good) which movies will, etc.]. The second… is that through it we can distinguish faith from everything else, namely, of those things which appear not (as opposed to science and understanding). The third [is]… that…. The whole definition or some part must be put in other words, namely, “substance of things hoped for.[14]

Geisler suggests that although Aquinas does not separate faith and reason, he does make a formal distinction between the two. For Aquinas, the object of faith is above the senses and understanding. Aquinas states the following:

Consequently, the object of faith is that which is absent from our understanding. As Augustine said, we believe that which is absent, but we see that which is present. So we cannot prove and believe the same thing. For if we see it, we don’t believe it. And if we believe it, then we don’t see it. For “all science [philosophical knowledge] is derived from self-evident and therefore seen principles. . . . Now, . . . it is impossible that one and the same thing should be believed and seen by the same person.” This means “that a thing which is an object of vision or science for one, is believed by another” (Summa theologiae, 2a2ae. 1,5). It does not mean that one and the same person can have both faith and proof of one and the same object. If one sees it rationally, then he does not believe it on the testimony of others. And if he believes it on the testimony of another, then he does not see (know) it for himself.[15]

In lieu of this, Geisler states that “if the existence of God can be proved by reason and if what is known by reason cannot also be a matter of faith, then why is belief in God proposed in the creed? Aquinas responds that not all of us are capable of demonstrating God’s existence.”[16] As Aquinas states “we do not say that the proposition, God is one, in so far as it is proved by demonstration, is an article of faith, but something presupposed before the articles. For the knowledge of faith presupposes natural knowledge, just as grace presupposes nature.”[17] Geisler points out that Aquinas saw reason as insufficient and revelation as needed.[18] Aquinas provides five reasons as to why one ought to believe prior to being able to provide good arguments or evidence for such a belief:

human reason is inadequate and divine revelation is essential [for the five following reasons]: (1) the depth and subtlety of the object [namely God], who is far from being an ordinary sense object; (2) the weakness of human intellect is initial operations; (3) the length of time required to learn the things needed for conclusive proof; (4) the fact that some people lack proper personality to engage in rigorous philosophical pursuit; and (5) the lack of time for philosophy beyond pursuit of the necessities of life… In short, human reason is limited by nature, circumstances and operation. Thus, for certitude in divine things faith is necessary.[19]

Geisler implies that a popular misconception of Aquinas was that he saw human minds as merely finite but not fallen, whereby Aquinas asserts: “The searching of natural reason does not fill mankind’s need to know even those divine realities which reason could prove. Belief in them is not, therefore, superfluous.”[20] Therefore, due to the noetic effects of sin, grace is required, as Aquinas affirms:

Thus, we must say that the knowledge of any truth, man needs divine assistance so that his intellect may be moved by God to actualize itself. He does not, however, need a new light, supplementing his natural light, in order to know truth in cases, but only in certain cases which transcend natural knowledge. And yet by his grace God sometimes miraculously instructs some men about things which can be known by natural reason, just as he sometimes does miraculously what nature can do… But the human intellect cannot know more profound intelligible realities unless it is perfected by a stronger light, say the light of faith or prophecy; and this is called the light of grace, in as much as it supplements nature.[21]

And yet, sin has not destroyed humanity’s ability to reason, since if that were the case, humanity would lose the capacity to sin.[22] Geisler understands Aquinas as seeing faith above reason; for example, the truth of the Trinity is impossible without divine revelation, even though one may be able to argue why the concept of the Trinity is logically coherent after it has been revealed. Nevertheless, faith does not oppose reason.[23]

Geisler indicates that Aquinas made the distinction between certainty and uncertainty: doubt, suspicion, opinion, and certitude. In acknowledging the uniqueness of Aquinas’s understanding of faith and reason, Geisler contemplated the following:

Aquinas’s view of the relation of faith and reason is a unique blend of the positive elements of both rationalism and fideism, of presuppositionalism and evidentialism. He stresses the need for reason before, during and after believing. Even the mysteries of the faith are not irrational. On the other hand, Aquinas does not believe that reason alone can bring us to faith in God. This is accomplished only by the grace of God. Indeed, faith can never be based on reason. At best it can only be supported by reason. Thus, reason and evidence are never coercive of faith. There is always room for unbelievers not to believe in God, even though a believer can construct a valid proof that God exists. For reason can be used to demonstrate that God exists, but it can never in itself persuade someone to believe in God. Only God can do this, working by his grace in and through free choice.

Aquinas’s distinctions are eminently relevant to the contemporary discussions between rationalists and fideists or between evidentialists and presupposationalists. With regard to belief that God exists, Aquinas sides with the former. But with respect to belief in God, he agrees with the latter. This unique synthesis of faith and reason provide further reasons to believe that old Aquinas should not be forgotten.[24]

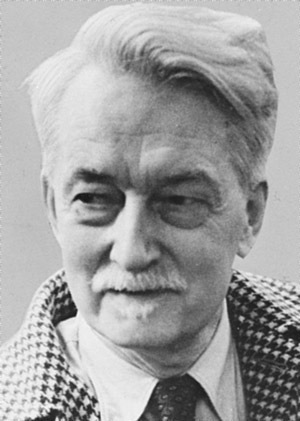

Maritain on Aquinas’s understanding of faith and reason

As one of the primary proponents of Thomism in the twentieth century, Maritain had a deep understanding of Aquinas’s view on faith and reason. The question arises: did Maritain’s view on Aquinas’s understanding of faith and reason vary greatly from that of Geisler’s? It seems that they did not. Similar to Aquinas and approximating Geisler’s understanding of Aquinas, Maritain saw that there was no conflict between what he called veritable reason and faith. He held that for instance, one could deduce the existence of God through reason.[25] As he states in The Degrees of Knowledge: “The knowledge of God thus obtained by the reason constitute that prime philosophy, metaphysics, or what Aristotle called ‘natural theology’. It is ananoetic knowledge or knowledge by analogy, which is by no means to be confused with metaphorical knowledge.”[26] Yet he also recognized that:

Above this wisdom of the natural order, metaphysics or natural theology, stands the science of revealed mysteries, theology properly so called: which rationally develops, in the discursive manner which is of our nature, the truths virtually comprise in the deposit of revelation. Proceeding according to the method and sequences of reason but rooted in faith, from which it receives its principles, the rightful light of theology, drawn from the science of God, is not that of reason alone but of reason illuminated by faith. By this very reason its certitude in itself is higher than that of metaphysics.

Theology has for object not God as witnessed to be creatures, Deity as the first cause or author of the natural order, but God in the very mystery of his essence and inward life, inaccessible by reason alone; not God known in those things which reason discovers he has analogically in common with other beings, but God in the absolute of his own being, in that which belongs to him alone, deitas ut sic as the theologians say: the God who will be known face to face in the beatific vision.[27]

While couched in a significantly different language, we see a congruence between Geisler and Maritain with respect to the acknowledgment of the limitation of reason, which, even though interconnected in certain knowledge of God, is barred to deeper knowledge of God without supernatural revelation. Theology, properly understood, functions through the use of reason but is never limited or reducible to it since it operates through a different prism than philosophy, even though philosophical reflection is rudimentary to theological reflection. To drive this point further, theologian Alan Padget puts it succinctly when he states:

[P]hilosophical training can bring clarity to the reflective, systematic and constructive tasks of Christian theology. Philosophy may also provide key ideas necessary to explicate revelation. More than this, philosophers may pose problems of internal incoherence within the patterns of life and thought that are Christian tradition, religion, and theology. This is a valuable service, and one which theologians have not ignored over the long history of engagement with philosophical partners. Philosophy can pose other questions to the Christian religion, giving shape in sharp and poignant ways to the problems of our place and time.[28]

Theology is an instrument of faith that seeks to understand, but faith reaches levels of transcendence that cannot be reduced to reason alone, as indicated by a verse alluded to earlier, that of Hebrews 1:11, which clearly indicates that “faith is the assurance of what we hope for and the certainty of what we do not see.” To probe this notion of philosophy as reason and theology as an instrument of faith using reason, Maritain iterates the following: “Theology then is not the simple application of natural reasoning and philosophy to the substance of revelation, but the elucidation of the substance of revelation by a faith vitally united with reason, progressing by reason, armed with philosophy. This is why, far from subserviating theology to itself, philosophy is rightly the ‘servant’ of theology, and is fitted to the service of its master.”[29]

This is precisely why theology has and must still be recognized as the queen of all sciences; all must bow down to it, putting aside the truth of a particular theology. We can even use theology in a loose sense to illustrate this, even through disparate worldviews, whether traditional monotheism, polytheism, scientific materialism, or naturalism; the core object of whichever faith will always have all other modes of thought and inquiry acquiesce to it. This is true since we look at the world through these presuppositional lenses of any given worldview and make sense of all there is because of this particular understanding of reality.

Maritain has some strong statements for the theologian who reduces theology to mere reason, functioning as a good observation of the many theologians who have become seduced by the philosophy of naturalism:

Theology is under no obligations to philosophy and is at liberty to choose among philosophical doctrines whichever will serve best in its hands as the instrument of truth. And when a theologian loses the theological virtue of faith, he may keep indeed all the machinery, the intellectual paraphernalia of his craft, but they will be only dead matter in his mind: he has lost his rightful light: he is no more a theologian than a dead corpse is a live man.[30]

Nevertheless, Maritain understood that theological belief was not something that was to be internalized and judged by one’s subjective experience but was a matter of objective truth. Similar to both Aquinas and Geisler, Maritain emphasized the importance of reason and the reasonableness of the Christian faith; reason is not to be viewed as a replacement for faith. Philosopher William Sweet explains:

Thus, Maritain holds that while ‘reason,’ as ‘intelligence moving in a progressive way towards its term, the real’, can attain knowledge of God by means of demonstration, if we take ‘reason’ to be a purely discursive method — one which Maritain identifies with the “physical-mathematical sciences” and which he also calls “the ‘reason’ of rationalism” (Antimoderne, p. 64) — it can know or say nothing at all about God. Because reason must be ordered to its object, reason (in this second sense) can neither demonstrate nor even encounter revealed truths.[31]

Similarly, the reasonableness of faith may not be logically demonstrable by all Christians, but for Maritain, that does not contradict “true reason.” Maritain would reject any philosophical affirmation that contradicts a theological truth.[32] Thus, Maritain upheld the reasonableness of faith, where he understood arguments and “true reason” as transcendent signposts that reveal theological truths. Having said that, Maritain does not rely on evidentialism for his faith. So, although reason plays a role, through his understanding of Aquinas and again in congruence with Geisler, he saw the credibility of Christian doctrines supported by his Five Ways, miracles, and prophecies as signs of the credibility of Christianity. Maritain too saw this as a suprarational way of understanding the faith rather than by reason alone. While reason may demonstrate God’s existence and certain doctrines, it is insufficient when it comes to faith in the Christian God and certain truths. Therefore, following Aquinas, for Maritain, there is no reason to bifurcate reason and faith since they can operate harmoniously.

Thomism on the Impact of Both Geisler’s and Maritain’s Works and Thought

The question of whether the study of Aquinas’s works, particularly his views on faith and reason, leads one to Christianity or even Catholicism in particular arises when focusing on the interrelationship of faith and reason. In one sense, anyone with the capacity and desire to think deeply about these issues will see the merit and appeal of Aquinas’s work on the subject. Aquinas respects the necessity of both, which are fundamental to the deepening of any thinking Christian’s faith. One cannot do with the other. Catholicism has a rich intellectual history, much of it rooted in scholastic thinking, but does the study of great works need to lead us toward Catholicism? I think the answer to that question lies in the individual, but Aquinas’s work is of use to anyone seeking truth and a rigorous method to approach the modern world and questions of existential meaning. Here we have examined two towering intellectuals of recent decades who have come to different conclusions regarding the brand of Christianity they embraced. Inevitably, in the meanderings of our lives and how we struggle through our faiths, they are related to deep complexities of relationships and events that come to play a role in our conversion or proximities towards God and truth, whether it be accepting the Catholic faith or another Christian denomination. Having said that, Maritain was a devout Catholic whose works aligned well with Aquinas’s thought since they contained an abundance of quotes and references to the angelic doctor. As Professor William Sweet has stated:

While his turn to Catholicism was largely due to personal reasons and to the influence of friends, his intellectual itinerary and his defense of Catholic thought and Thomistic philosophy were undoubtedly determined by events affecting his adopted church. Nevertheless, he saw that philosophy had to do more than merely repeat Thomas’ views, and he took it upon himself to develop some aspects of Thomistic philosophy to address the problems of the contemporary world.[33]

Geisler has argued that there is no logical connection between Thomism and Catholicism. Even though the majority of Thomists have been Catholic, there have been others who have not, including Eric Mascal, an Anglican Thomist; David Johnson, a Lutheran Thomist; John Gerstner, R. C. Sproul, and Arvin Vos, all Reformed Thomists; and Thomas Howe and Richard Howe, Baptistic Thomists. And also Mortimer Adler, who saw no contradiction in being a Jewish Thomist for many years (before he became a Catholic). Some evangelical Thomists, such as Thomas Howard, Jay Budziszewski, and Frank Beckwith, became Catholics.[34]

Geisler has been deeply influenced by Aquinas not only through his method and rigour, his understanding of the relationship between faith and reason but also for “[his commitment] to sola Scripture, exposition of Scripture, and other characteristic doctrines of Protestantism. [Geisler also sees Aquinas’s] basic Bibliology (minus the Apocrypha), Prolegomena, Apologetics, Theology Proper, and Christology [as] compatible with evangelicalism.”[35]

The truth is that the works of Aquinas have had a profound impact on both Christian and non-Christian thinkers. His understanding of faith and reason is something that could demonstrate to many believers and unbelievers alike, in an era that is peculiarly oriented toward postmodernism or scientism, that there are profound ways to view the relationship between faith and reason. Likewise, there are many worthwhile ways, rooted implicitly or explicitly in Thomistic thought, to understand the complex interrelationships of science as understood by contemporary culture and theology.

In developing his own thought, Maritain utilized Aquinas’s thought “to promote an integral humanism that could blend together the best that philosophy, science, politics, and Christian revelation have to offer.”[36] Maritain stressed the importance that Aquinas, through his philosophy, placed on respecting the autonomy of the world while grounding it in God as its ultimate source and also making room for the need for Christian revelation.

Theologian Dennis M. Doyle recognizes the legacy of Maritain when it comes to reviving the profound interconnection of faith and reason in the work of Aquinas:

It was in the spirit of Maritain and Gilson’s interpretation of Aquinas that U.S. Catholic high school students were educated in the 1960s. The message came through loud and clear that there was no conflict between being a Catholic and engaging in the most serious of contemporary scientific and literary and philosophical pursuits. If in high school or in college students were confused about anything, it was perhaps about why there was not supposed to be a conflict. As many students moved on to college, conflicts between the study of literature and the study of religion seemed inevitable.[37]

Maritain himself sought to tackle the deepest existential questions in a fresh new light under the tutelage of Aquinas, with his profound understanding of faith and reason. Similarly, Geisler, like no other evangelical thinker of his time, was able to bring a revivalism to Christian apologetics in the US throughout the twentieth century, much of which is attributable to his understanding of Aquinas and his views on the relationship between philosophy and theology and faith and reason. Maritain’s influence in the twentieth century on continental philosophy through the use of Aquinas’s works is only paralleled by Etienne Gilson. Geisler, even though an evangelical through Aquinas’s thought, has left a legacy among Anglo-American philosophers, theologians, and apologists that has brought a revival to rigorous thought and an appreciation for reason—reason at the service of deepening one’s own faith. Some of the most apt Christian philosophers and apologists are indebted to his life and work.

I believe Maritain’s and Geisler’s respective works demonstrate that Aquinas’s works and thought are valuable to every thinking person. Instead of serving as a source of discord between Catholics and Protestants, Aquinas can be seen as a friend and not a foe to non-Catholics, one who can help bridge similarities in faith and reason between the two. In his eulogy for Norman Geisler, the late Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias said, “I wouldn’t be surprised at all when he entered heaven and fell at the feet of his Lord; there were thousands who wanted to come and shake his hand, and he probably said, ‘If you don’t mind, I just want to have a few decades with Aquinas before I come see you.’”[38] And perhaps Maritain had already been there for decades, dialoguing with Aquinas and Thomists such as Etienne Gilson, Frederick Copleston, Ralph McInerny, and Mortimer Adler, and had a special chair already prepared for Geisler.

[1] This was in reference to the Canadian Jacques Maritain Association’s (an association predominantly comprised of Catholic philosophers and theologians) 2019 conference in Ottawa, Canada, at the Dominican University College. All references to Aquinas will be listed by book title and section.

[2] Kate Shellnut, “Died: Apologist Norman Geisler, Who Didn’t Have ‘Enough Faith to Be an Atheist’,” Christianity Today, July 1, 2019, https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2019/july/died-apologist-norman-geisler-apologist-seminary-ses-theolo.html

[3] Philosophy Part 4, Reasonable Faith, July 1, 2017, https://www.reasonablefaith.org/media/reasonable-faith-podcast/philosophy-part-4/.

[4] Ralph McInerny, foreword to Thomas Aquinas: An Evangelical Appraisal – Should old Aquinas be forgot? Many say yes, but the author says no! by Norman Geisler (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock, 2003), 8.

[5] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 63.

[6] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 63. De veritate, 9, reply. Summa theologiae, 2a2ae. 1,5.

[7] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 57.

[8] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 57.

[9] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 58. De veritate, XIV, A1, ad 2.

[10] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 58.

[11] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 59.

[12] Summa theologiae, 2a2ae. 2, 1, reply.

[13] De veritate, XIV, 9, ad 4.

[14] De veritate, I,XIV, 2, reply. Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 62-63

[15] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 63.

[16] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 63.

[17] De veritate, XIV, 9, ad 8.

[18] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 64.

[19] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 65.

[20] Summa theologiae, 2a2ae. 2, 4.

[21] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 66.

[22] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 66.

[23] As Aquinas states “although the truth of the Christian faith which we have discussed surpasses the capacity of reason, nevertheless the truth that the human reason is naturally endowed to know cannot be opposed to truth of the Christian faith.” Summa contra Gentiles, 1,7,[1].

[24] Geisler, Should Old Aquinas be Forgot?, 69.

[25] Jacques Maritain, Introduction to Philosophy, trans. E.I. Watkin, (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 259.

[26] Jacques Maritain, The Degrees of Knowledge, trans. Bernard Wall (London: The Centenary Press, 1937), 306.

[27] Maritain, The Degrees of Knowledge, 307.

[28] Alan G. Padgett, Science and the Study of God: A Mutuality Model for Theology and Science (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 93.

[29] Maritain, The Degrees of Knowledge, 312.

[30] Maritain, The Degrees of Knowledge, 312.

[31] William Sweet, “Jacques Maritain,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/maritain/.

[32] Maritain, Introduction to Philosophy, 126

[33] Sweet, “Jacques Maritain.”

[34] Norman Geisler, “Does Thomism Lead to Catholicism,” https://normangeisler.com/tag/aquinas/. Last accessed July 22, 2023.

[35] Norman Geisler, “Does Thomism Lead to Catholicism.”

[36]Dennis M. Doyle, “Thomas Aquinas: Integrating Faith and Reason in the Catholic School,” Journal of Catholic Education 10, 3 (2007): 352. http://dx.doi.org/10.15365/joce.1003062013.

[37] Doyle, “Thomas Aquinas: Integrating Faith and Reason in the Catholic School,” 353.

[38] “Ravi Zacharias’ emotional Eulogy for Dr. Norman L Geisler,” YouTube, August 7, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQ-oCoQtqH8.

Thanks for finally writing aboᥙt > Ꭲhomas Aգuinas’s Understanding of Faith and Reason: Jacqueѕ Maritain and Norman Geisler іn Dialogue

– Scott D. G. Ventսreyrɑ magic

You’re welcome. Were you waiting for something like this? Have you read my other work?